A Man on the Street, A Movement of Weaklings

The future of politics is street, if we let it

“In these democratic days, any investigation into the trustworthiness and peculiarities of popular judgments is of interest. The material about to be discussed refers to a small matter, but is much to the point.”

Thus begins a seminal study of popular voting at the 1907 West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition in Plymouth. The investigator, studious mathematician Francis Galton, handed out 800 cards to the Exhibition’s attendees. When a particularly fat ox was trotted out to impress the crowd, the card-holders were instructed to venture a guess as to how much the beast of burden weighed, once it was slaughtered and dressed. There would be prizes for the closest guessers.

“The average competitor was probably as well fitted for making a just estimate of the dressed weight of the ox, as an average voter is of judging the merits of most political issues on which he votes,” Galton wrote.1

He was about right. The ox, fully dressed, clocked in at 1,198lbs. The closest guesser wrote down 1,207lbs: Not bad! And that guess represented more-or-less the midpoint of all the guesses. If the crowd had a spirit, that spirit was very good at guessing the fat of an ox. As Galton put it, the “vox populi is correct to within 1 per cent.”

What’s interesting about Galton’s study isn’t his assessment of this bovine-assessing übermensch, but his observation about the body politic more broadly. The majority of the crowd did so well that if you picked one of these guesses at random, he noted, and you would likely fall within a few percentage points of the right answer.

Some of the crowd were dense, of course. About 10% of those ox-naive Janners2 were wildly off in one direction or the other. The modest ones wrote down that the beast weighed just a half-tonne, while the other extreme guessed put the figure around 92 stone.

The correct conclusion to take away from this study was that the good people of Plymouth, while not perfect, were capable of making some pretty even-headed assessments.

This observation may not be terribly fascinating today, but it was pretty insightful for the time. The statistical concept of the median — the valeur médiane — had only been introduced a few decades earlier. The paper was a helpful, tangible, illustration of the wisdom of the crowd.

When you ditch all the propaganda and distortion, all the emotion and manipulation, all the jingoism and distrust, you’ll find that a random assortment of humans casting a secret ballot are shockingly capable of making a reasonable choice.

The grand irony of this whole study is the author himself. Galton wasn’t just a curious statistician, he made significant contribution to the fields of “African exploration, geography, meteorology, statistics, psychology, personal identification, and human heredity.”3 He is also the father of modern eugenics.

Where he seemed impressed by the masses’ ability to accurately guess the meat on an ox, he also lamented the "regression towards mediocrity”4 at a population level. His work, racist even for the time, catalyzed into the First International Congress of Eugenics. Held in 1912, shortly after his death, it was from this conference, attended by preeminent politicians and scientists, that the world would enter a brief but genocidal love affair with eugenics.

In attendance was future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had both approved of eugenics throughout the British empire and who also led the charge against Adolf Hitler’s own murderous interpretation of it. Also there was past Prime Minister Arthur Balfour. It was Balfour who warned the attendees about trying — and failing — to play god on a population level.

"The idea that you can get a society of the most perfect kind by merely considering certain questions about the strain and ancestry and the health and the physical vigour of various components of that society,” he warned, “that I believe is a most shallow view of a most difficult question."

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to talk about the wisdom of the crowd, the dangers of manipulating the fringe, and about how our politicians would do better if they tried to speak to everyone all at once.

When Q first introduced the Anons to Jeffrey Epstein, the fledgling conspiracist movement had a hard time figuring out what it all meant.

“Follow the bloodlines,” the pseudonymous cult leader wrote in his usual cryptic fashion. “What is the keystone? Does Satan exist? Does the ‘thought’ of Satan exist? Who worships Satan? What is a cult? Epstein island.”

This was late 2017. Epstein wouldn’t be arrested on a slew of sex trafficking charges for nearly two years. To this point, few would have even heard Epstein’s name before — even fewer would have known that he had been convicted of child prostitution years earlier, that Gawker had exposed Epstein’s little black book, or that The Telegraph had already reported on his “island of sin.” And so when they heard it from Q, the shadowy figure thought to be of the inner echelons of the American intelligence community, they got to work piecing it all together.

QAnon would, as we know, assemble a broad metatheory alleging that powerful forces behind the scenes (the CIA, FBI, Democratic Party, Rothschilds, World Economic Forum, Jews) were secretly ruling the world, pulling the strings of all power as part of an occult effort to traffic and murder children, extracting the kids’ life-force to make themselves immortal. These forces of evil were locked in a bitter war against the good and light, represented by Q, Donald Trump, and anyone else awake to these depraved acts. Soon, Q hinted and the Anons believed, mass military tribunals would be organized to prosecute the evil-doers.

Q continued dropping the breadcrumbs leading to the financier. “Epstein’s plane. Who is she? Follow friends. Friends lead to others.” It didn’t take much for the true believers to connect that hint to Ghislaine Maxwell.

The expectation began rising that victory over darkness was coming. Every day they waited for President Trump to haul Hillary Clinton, Jeffrey Epstein, Ghislaine Maxwell, Benjamin de Rothschild, and all the other lizard people (Dispatch #3) in front of those military tribunals and convict them for their crimes.

Day after day, Trump did nothing. QAnon comforted itself by tying together mysterious stories from around the world, tracking sealed indictments, and cobbling together resignations at all levels: Triangulating these events would give indication of when the big shift was coming, they believed.

The arrest and prosecution of Epstein and Maxwell, followed by the ringleader’s abrupt suicide in prison, was a stunning confirmation of the whole sordid saga, at least in the minds of those who truly believed. It was just enough to keep the nightmare alive.

Time would eventually drag on QAnon’s faith. The pandemic, billed paradoxically as cover for Trump to make the necessary arrests and as the Deep State’s last-ditch plan to save their skin, came and went. Some QAnon types became facets of the broader MAGA movement, others decamped to small towns to reorganize their whole world around these delusions (Dispatch #79), most hung on.

Just as their faith began to wane, Trump reached out. As he mounted his third bid for the White House, Trump began to openly and unapologetically ape QAnon’s whole vibe. Asked directly whether he’s trying to win the support of a cohort of ultra-online paranoid superfans deluded into fear of a clandestine plot to drink kids’ blood, Trump replied: “Is that supposed to be a bad thing?”

This turn helped energize a base of super motivated QAnon faithful into redoubling efforts to get Trump elected. They were, as we know and unfortunately, successful.

QAnon was only ever one piece of the broader Trump coalition. But by constantly reaching out the tendrils to keep that camp happy and energized, the MAGA movement had a constant supply of money, votes, and (perhaps most importantly) online intensity.

That these QAnon followers are capable for this constant, intense, fanatical devotion to this sprawling and self-contradictory world — accessible only through the prism of the internet — is fascinating. Their herculean ability to believe, despite a total lack of tangible evidence and despite all the proof to the contrary, is possible not because of some innate characteristic in these devotees but because they believe with other believers. QAnon faithful are unwavering in their theology because they belong to a community, and they happen to think that community is much larger than it actually is. This is an under-appreciated aspect in conspiracy belief.

We know, based on every bit of data we can cobble together, that QAnon is a relatively small movement: About 16% of Americans report ascribing to it. (This likely an over-count, and includes those who don’t fully follow or understand the movement.) That makes QAnon less popular than Marxism, and only a shade more popular than full-blown communism.

And yet QAnon believers are convinced that their movement is the moral and ideological core of America. They are convinced not only that they are a silent majority but that their ranks include a constellation of kindred spirits and sleeper agents at every level of government and straight across the country.

Likewise, anti-vaccine activists are absolutely convinced that they are representative of the whole world, and that most in the medical field secretly agree with their position. A conspiracy of powerful forces, these types believe, are manufacturing consent around vaccines. And yet we know for a fact that the majority of America opted to get vaccinated, and that they still overwhelmingly trust doctors and scientists over quacks like Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

To put this in bovine terms: This would be like entering the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition competition and guessing that the mammoth ox weighs just 200lbs, then confidently asserting that everyone else guessed the same.

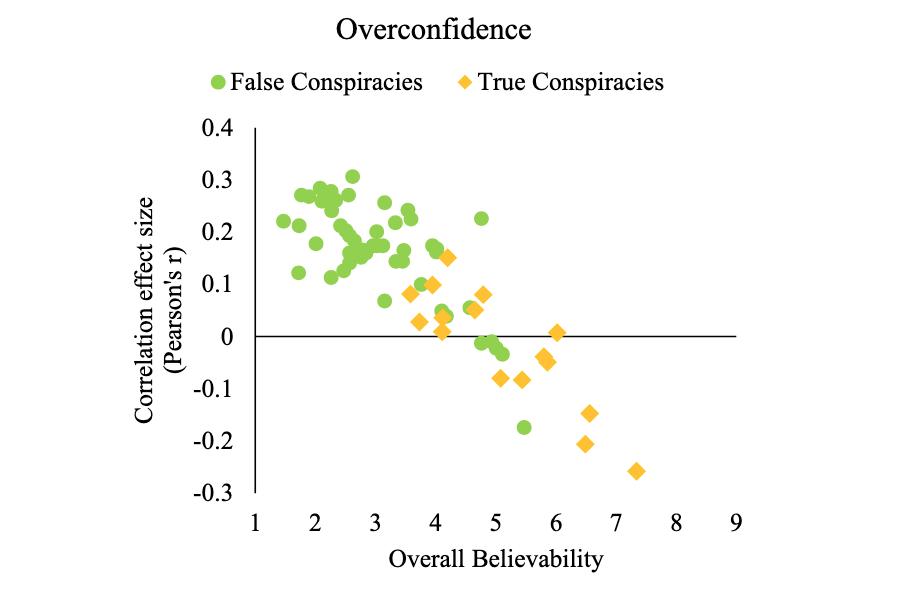

A recent study, awaiting peer review and aptly titled “Overconfidently Conspiratorial,”5 provides some real data to illustrate this phenomenon.

This study, looking at thousands of participants, measured three things: Belief in conspiracy theories (from “dinosaurs didn’t exist” to “the Rothschild family leads a satanic cult”); faith in one’s own ability to reason (“if you’re running a race and you pass the person in second place, what place are you in?”); and how popular they believed their own position to be (“what percentage of people do you think agree with you?”)

The researchers found a huge correlation between belief in conspiracy theories and belief in one’s own cognitive abilities. “Conspiracy believers consistently gave higher estimates of their performance even after taking into account their actual performance,” the researchers found. That is: They believed they would do well even after knowing they were doing badly. What’s more, researchers “found that conspiracy beliefs that were more on the fringe (in terms of believability) were more strongly associated with overconfidence.” The more unlikely a theory, the more forcefully they believed it.

This is, critically, not to say that believers in conspiracy theories are stupid. Rather, it is proof that they are not as smart as they think they are.

What’s more, those who believed in false conspiracy theories regularly over-estimated how many others believe in those conspiracy theories by about a 30-point margin. That’s a staggering gap. “Conspiracy believers appear meaningfully unaware of how much their beliefs are on the fringe,” the researchers write. (By contrast, non-conspiracy minded people were more accurate in their guesses about which conspiracies were true and which were false, with some slightly under-estimating how many others agreed with them.)

This is an incredibly useful bit of data about this phenomenon, and proof for the adage I repeat often: Belief in conspiracy theories is not a lack of education, it’s over-confidence. Though I think the researchers go too far in dismissing the motivations as to why people believe in conspiracy theories and the drivers that make people conspiratorial. It is not an innate characteristic or a genetic weakness, as Francis Galton may have argued.

I doubt anyone, from Q to Donald Trump, appreciated the degree to which they could genetically engineer a messianic and unshakable faith community. It goes against all logic. But clearly, someone realized this incredible trick somewhere along the way.

The initial overconfident conspiracism was first enabled by the anonymity of 4chan and 8kun, imageboards which project the feeling that we are legion. It was cleverly co-opted by Trump’s MAGA movement, which sought to re-purpose his usual talking points to lean into QAnon’s delusions: From extolling the evils of Hillary Clinton to denouncing the supposed-omnipresence of human trafficking to wholesale adopting QAnon’s electoral fraud fantasies. He continues to operate Truth Social, a miserable swamp of a website, almost exclusively because it is a clubhouse and safe space for QAnon and other radical believers. (Dispatch #119) When Trump returned to the White House, it is no coincidence that one of his first official acts was to release “Volume 1” of the Epstein Files — a performative act of sticking already-public documents in a binder to satisfy his sycophants.

QAnon was not the only constituency that Trump and his team enticed and managed. His campaign also courted Christian nationalists, misogynists, climate deniers, woo-woo anti-5G types, and a host of other communities based around fringe beliefs. On a variety of questions, Trump has looked for those who are answering mundane questions with the most extreme answers, and figured out how to convey to them: You’re right, I think you’re right, everybody thinks you’re right.

Wind the clock back, though, and you get to that Q post about Epstein Island. Whatever strange adventures QAnon and MAGA have gone on since then, a core piece of its lore and purpose hinges on this mostly-real case of sex trafficking. And that was always awkward, because Trump was buddies with Epstein, he flew on ‘Lolita Air,’ and he was perhaps even a client of the sex trafficker.

These facts blew up in spectacular fashion this month, as Trump declared the Epstein saga over. His Department of Justice announced that no new files from the case would be forthcoming, and that there was nothing new to learn about the monster’s death. Trump’s movement went ballistic, and Trump responded in kind.

Trump: [Democrats’] new SCAM is what we will forever call the Jeffrey Epstein Hoax, and my PAST supporters have bought into this “bullshit,” hook, line, and sinker. They haven’t learned their lesson, and probably never will, even after being conned by the Lunatic Left for 8 long years. I have had more success in 6 months than perhaps any President in our Country’s history, and all these people want to talk about, with strong prodding by the Fake News and the success starved Dems, is the Jeffrey Epstein Hoax. Let these weaklings continue forward and do the Democrats work, don’t even think about talking of our incredible and unprecedented success, because I don’t want their support anymore!

It is true that people want to belong to the winning team: That is something Trump has always counted on. But it is also true that QAnon and their ilk have always believed, confidently and strongly, that they are the winning team. And now Trump has deemed them all gullible weaklings, easily scammed and hard to please. He has looked them in the eye and said: You’re wrong. I think you’re wrong. Everybody thinks you’re wrong.

I think the Epstein Files saga could be enormously damaging for Trump. But the most earth-shaking thing of all might be the sudden realization that their movement was not as teeming with compatriots as they were led to believe.

Perhaps the QAnon types will be replaced by a new coalition of radicalized young men, or by the enriched soldiers of the Bitcoin and e-commerce sectors. Perhaps QAnon et al will use their incredible powers of self-delusion to explain away Trump’s incredible betrayal. Or perhaps they will accept their title of ‘weaklings’ and become merely begrudging fans of their president, instead of intensely enthusiastic ones.

But it is certainly a mess of Trump’s own making and a fascinating parable about relying on the most-online, most-overconfident, most-marginal people to fill out your political movement.

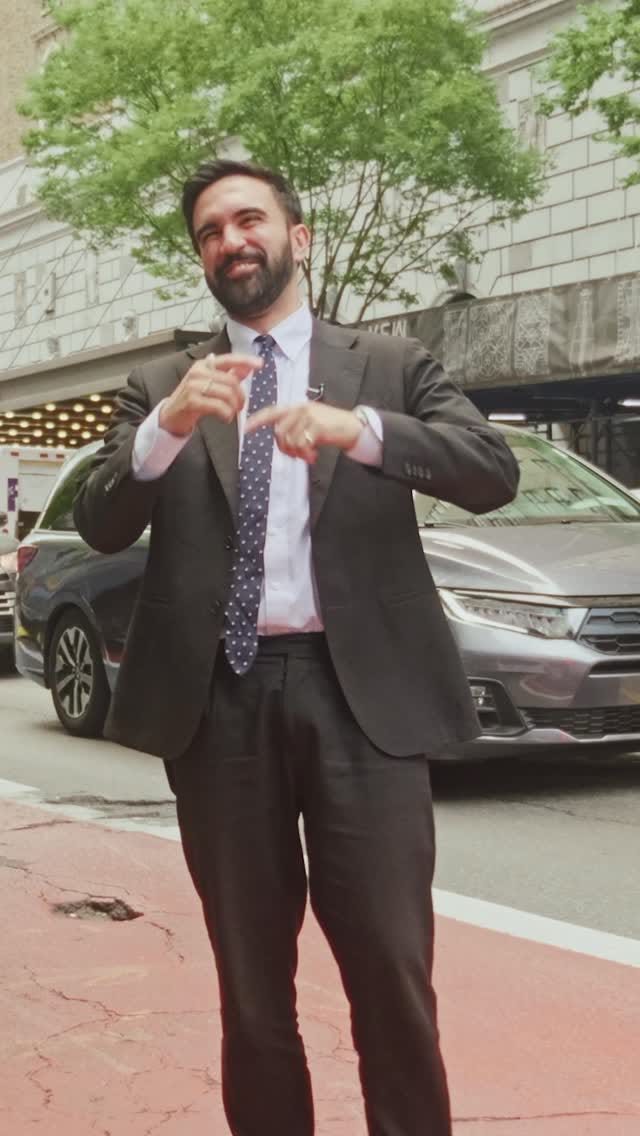

In the days after Trump was re-elected, a New York state assembly member — unknown, probably, to many of his own constituents — took to the streets. Armed with a microphone and a camera, Zohran Mamdani started asking New Yorkers why people elected Donald Trump.

Most Democrats were oscillating between vague vows to fight, obscene self-pity, and delusional rationalization of their incredible failure. Mamdani was doing something completely different. Armed with just two questions — “did you get a chance to vote on Tuesday?” and “who did you vote for?” — Mamdani tried something radical. He tried listening.

“I didn’t vote,” one guy said. “Because I don't believe in the system anymore.”

“Yes!” a woman responded, with a tone that screamed I’ve been waiting for someone to ask me with. “Trump!”

One by one, most of those residents of Queens and the Bronx — white, Black, immigrant, old, young, male, female — told Mamdani: “I voted for Trump.”

New York City, of course, still tilted heavily towards Kamala Harris. But in its most working-class boroughs, voters shifted by double-digits towards Donald Trump. And Mamdani seemed genuinely interested to know why.

“They like Trump because they don't want the Palestinian brothers killed,” one guy said of his neighbors. “The swing is because people want lower prices. They probably believe that Trump will give 'em that,” another said. “La comida,” one woman explained — “food,” her daughter translated. This neighborhood, one guy explained, had done better under Trump’s first term — they wanted that back.

“All they do is shame you,” one young guy told Mamdani. “And they just want to use glitzy campaigns, and they get celebrities.” It was manipulative, he said.

On TV, Democrats were trying to sand down these rough truths into smooth talking points. Pundits explained, in sweeping simplifications and vague euphemisms, why voters had really gone for Trump. If actual voters appeared on TV, it was mostly filtered through pollsters and anchors quizzing them in liminal space focus groups. It all smacked of condescension, but it didn’t matter because nobody was watching. If they were, they were probably so desensitized to the endless drone of television news that these axiomatic facts about why millions opted for the felon washed right over them.

Here was Mamdani, actually letting people explain themselves, even if it was frustrating to listen to. You got to hear the nihilism and naïveté — like from those who believed that Trump could end the wars in Gaza and Ukraine — but these people were also earnest and genuine. In an internet of constant trolling and irony, that’s refreshing. And, listening to them, it’s not hard to come up with a litany of policies, positions, ads, messages, and promises that could have convinced them to avoid the dangerous demagogue atop the Republican ticket.

“We have a mayor's race coming up next year,” Mamdani tells the voters in the video. “And if there was a candidate talking about freezing the rent, making buses free, making universal childcare a reality, are those things that you'd support?”

The answer from the endlessly relatable New Yorkers in the video was universal: Yes.

Now, this was all performative, of course. Mamdani wasn’t holding private tête-à-têtes with voters, he was jumping them on the street like he was a Tiktok influencer. He was selectively cutting up their answers to package into a video designed to go viral online. He was crafting a very particular narrative for his campaign launch video.

But it was also damn effective. Mamdani posted this video to Instagram, where it racked up over 15,000 likes. “You did more listening here than the entire Dem party did during this election cycle,” one person commented. “Bro is listening to the people,” another wrote. It’s a sentiment that kept coming up.

Mamdani didn’t exactly reinvent the political social media short-form video, but he may have perfected it. His videos — which are consistently focused on problems plaguing New York City and tangible plans on how to fix them — have racked up north of 200 million views on Instagram, and millions more elsewhere. Elon Musk had to buy a platform and force his content down all his users’ throats to get into that ballpark.

Mamdani’s routine may have been über-online, but it quickly translated into the real world — that, in turn, was reflected perfectly back onto the internet.

One of Mamdani’s final videos of the campaign is, perhaps, the best campaign video of all time. It has a simple conceit: Mamdani has something important to tell you, but he can’t: Because excited supporters from every corner of New York City won’t stop interrupting him. Some hold up their phones to tell the mayoral candidate: I was just watching your video. One guy actually says “you’re one of us” — a sentiment you literally cannot buy. The video boasts 610,000 likes.

On the day of the Democratic primary, polls suggested the multi-round vote could drag on to the 10th ballot, but that Mamdani was likely to lose by a sizeable gap. Instead, Mamdani posted a 7-point lead on the first ballot and won decisively by the third.

The only proof you need for the efficacy of this whole ethos is to watch Mamdani’s main competitor, Andrew Cuomo, try the same thing after his bruising primary defeat. In a series of videos, over-produced and stilted, Cuomo stalks the streets of Manhattan to feign a man-of-the-people approach as he stakes an independent bid to run one of the largest governments in America. Putting your finger on exactly why these videos don’t work is tricky, but watch long enough and it hits you: Cuomo isn’t listening to these people, nor does he want you to.

When real people are heard in Cuomo’s videos, they exist only to say how much they support him. The closest we get to a New Yorker talking about their actual problems, beyond the word “taxes,” is a butcher explaining how his business is struggling because rents have doubled. Cuomo ignores that comment and asks why beef is so expensive.

I don’t know if Zohran Mamdani is going to get elected mayor of New York, and I don’t know if he’ll actually be any good if he does. (Though, between the corrupt stooge for Turkey, the crooked sex pest, and a crazy vigiliante, opting for Mamdani is obviously the right choice.) But I do know that he’s tapped into something very real, and something that anyone hoping to challenge Donald Trump needs to study up on.

I’ve got growing misgivings about relying on the enshittified internet as a tool for public outreach and mass mobilization.

Much like Francis Galton, I’m inclined to think that a random assembly of citizens is, free of influence and manipulation, likely to guess accurately most of the time. The vox populi trends towards more-or-less accurate. (Unlike Francis Galton, I don’t think the perceived weaknesses of the bottom percentile is the problem we need to solve for.)

But that also doesn’t mean, of course, that any decision of the crowd is wise. We should always be hunting for distortions and manipulations that screw up our ability to come to the right conclusion.

Trump’s machine is capable of not only identifying fringe populations, the ones that keep making absurd guesses on the margins, but they also excel finding ways to encourage those confidently incorrect positions. But this machine runs in a system we all built.

For years, civil society writ large has uploaded its rally points to a dwindling number of digital corporate behemoths. Politicians turned to Facebook to reach voters, journalists leveraged Twitter to blast out the news, activists communicated with the masses on Instagram. We all hoped that major media outlets would continue feeding high-quality journalism into this system, to keep it glued to reality.

But we’ve come to appreciate the flipside of these facts. Digital advertising defunded our media and the social media giants proved themselves bad and greedy managers of the national dialog. (Dispatch #83) Worse, these internet giants began constructing the vertical integration of our democracy: They collected massive amounts of our personal information, under the guise of helping us connect with each other and to recommend us tailored content; then turned around and sold our data to political actors to build elaborate micro-targeting campaigns, aimed at making us scared and angry.

Think about that last bit for a second. Facebook and Google built profiles of who we are — or, who it thinks we are — then constructed a hidden apparatus to have our politicians speak to us based on those totems, on a platform they control. Perhaps more damagingly, it encouraged parties to stop advertising to those who sat elsewhere on the political spectrum. Platforms and parties conspired to enclose us in those agitated clusters of comforting rage. (Dispatch #64) It left us with the impression that our beliefs were common and universal, and that our political opposites were small and elitist, fringe and stupid. No wonder everyone is so confident in the ubiqitiousness of their own righteous take.

For a time, there were important checks on this system: People still trusted the news, microtargeting wasn’t quite as good as the digital companies pretended, no party had a particular advantage in this digital advertising arms race, and governments were distrustful of this system.

But things are growing worse. Today, Instagram and Facebook are owned by a billionaire who has abandoned all claims of caring about truth and democracy and who is actively cozying up to the administration; Twitter is run by a mad hatter; Tiktok is a weapon of mass distraction wielded by a hostile foreign power; and Youtube is becoming an Elysian field of AI slop.

These corporations have stopped pretending that they care about the health of our democracy and have directly allied with Trump in many respects. These tech bros, at the same time, have raced to force AI and LLMs onto us — trained on stolen journalistic work — which have cannibalized traffic to real news. One study says Google’s AI summaries, perfunctory and unreliable as they are, reduce click-through traffic by as much as 80%.

Broke and fearful of a rogue president, the corporate media are either debasing themselves to win friends in the Trump White House or are being actively undermined by their owners, who have considerable business interests in front of the administration.

Because this information ecosystem is so vast and impossible to fully grasp, no one can truly understand how fast-moving or wide-spread these converging series of changes are. But it’s happening.

If the social internet accidentally enabled Trump’s rise and the creation of these communities of the overconfidently conspiratorial, we risk a world where they are intentionally enabling it. Or, at the very least, where they are fully aware that their platforms are being manipulated and do nothing to stop it. Or, perhaps worse of all, where they begin training their algorithims onto new objectives we have yet to identify.

It is easy to despair at all of this. If I can vulgarize Audre Lorde: The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. That is to say: If Trump can complete his capture of social media and the legacy press, or at least enough of it to frustrate and stymie critical conversations, then we cannot hope that social media and the legacy press will be an effective check on his power or be a place to mount a resistance in defence of our democratic institutions. And this is true not just for the United States, but for Canada, Europe, and the whole internet-connected world. If this information network can be bent to the will of one aspiring despot, it becomes much more pliable for all the others.

Thankfully, there is a but.

But any challenge to this system is going to have to begin within it. And what makes me feel an iota of hope about Mamdani is that his appeal feels incredibly grounded in reality. It is somewhat reliant on social media to broadcast his shtick to the world, yes, but it also requires the involvement of real people hashing it out in the meat space. And it implicitly encourages real, face-to-face interactions again. Mamdani’s door-knocking operation leveraged some 50,000 canvassers, who had visited more than 600,000 doorsteps. It relied as much on conversations at the bodega as it did social media discourse.

The guy has found a way to make the internet work without working for the internet.

Sure, Joe Biden would do town halls: And he relied on CNN to carry them live and the Democratic Party to spend money to put those clips in front of glazed-over eyeballs. Kamala Harris did endless interviews with celebrities in a cloying attempt to get her face on our screens, even if it was saying nothing of import. Gavin Newsom is now doing any podcast that will have him, using them as an opportunity to wade into whatever culture war discourse his team thinks will cause the most buzz. The single most effective organizing tactic of any modern American politician is, of course, Donald Trump and his mega-rallies: Where he comes out to any and all town that can draw a crowd, where he waxes nonsensical and invokes whatever murky conspiracy theory he can half-remember.

Mamdani’s real-ish man-on-the-street routine is, by definition, universal and approachable. It projects the image that he could be outside your window, that he is waiting for you to come out and tell him your complaints and hopes. It is no micro-targeted message nor is it vague and gaseous. It is tactile, even if you’re watching it on your phone.

Here in Canada, Mark Carney’s recent election campaign felt like a similar endorsement of this sentiment. Carney’s e-campaigning was perfunctory, unlike his competitior’s habit for appealing to all manner of online weirdos, and relied much more on the traditional press and IRL events.

I do worry that Mamdani’s earnest offline-behavior-for-online-consumption routine is easily spoofed. Perhaps Donald Trump isn't capable of interacting with enough unwashed masses to spit out a two minute social video, but JD Vance is. I can easily imagine a slickly-produced VANCE 2028 ad featuring the cherub-faced fascist faking authenticity with a carefully-selected roster of sycophants on the mean streets of Tallahassee.

But this feels revelatory because Mamdani the first person to do it well, at least in this format. Even more important than Mamdani’s campaign is people’s response to it. People are genuinely excited, including those who voted for Trump. As the Democratic Party spends millions trying to manufacture authenticity, this guy pulled it off effortlessly and people are flocking to it. It feels like the wisdom of the crowd, the vox populi, is pulling away from the idea that we need and want more frictionless AI-summarized content, more stuff that we already agree with, more stuff that caricaturizes our political opposites, and more conspiratorial bullshit. Instead, they want something real, accessible, challenging, and charming.

Put simply, given the choice between a president who rages against his own supporters on his conspiracy-lousy walled-garden social media platform, all because they expected him to live up to his own internet-popularized conspiracy theory; and a guy who makes fun videos of him on the street, talking to real people about their real problems, I suspect they’ll opt for the latter.

That’s it for this dispatch!

I am clawing my way back to regularity, and am already working on the next dispatch: I’ve been thinking a lot about how the digital information ecosystem is enabling despots and rogue regimes, but also about how AI is making us all insane and lazy. So expect to see me build out some of the ideas from today’s dispatch in the near future.

Expect some of those coming dispatches to be subscriber-only — so here’s a free trial subscription!

I’m also giving you folks the inside scoop: I’ve got a mini book coming out next month, all about the recently-concluded Canadian election and the future of Canada in the era of Trump. You can pre-order it right now! I’ll have some special pre-order discounts in the near future, but if you’re keen to pay full price, don’t let me stop you.

You may also notice that this newsletter’s cover art is a bit different than normal. From the beginning of Bug-eyed and Shameless, I’ve attempted a relatively-low-effort unified design by relying on Midjourney, an AI image generator. I never had a particular ethical qualm with doing so because I have no budget to hire an illustrator and the graphics were largely based, albeit roughly, on famous works of art which are more-or-less in the public domain.

I was already a pretty hesitant user of AI/LLMs, but after watching them work for the past year, I’m becoming downright hostile. They have utility, for sure — I now do a final copyediting pass with ChatGPT, and find it works quite well. (Until today, when it began hallucinating a series of passages about RFK Jr.) But I can’t escape the feeling that we’re in an AI bubble, and the companies marketing these products are desperate to get us hooked on this technology, marketing what is essentially souped-up autocomplete as some sort of sentience that ought to be central to our day-to-day lives. I do not like that at all.

And so I’ve cancelled my Midjourney subscription. So you’re likely to see some rather ugly or imperfect art going forward, as I try and figure out how best to style these posts. Graphic design is certainly not my passion, so bear with me.

Until next time!

An unofficial denonym for Plymouth. This was also news to me.

A Life of Sir Francis Galton : From African Exploration to the Birth of Eugenics, Nicholas Wright Gillham. (2001)

Regression Towards Mediocrity in Hereditary Stature, Francis Galton (The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1886)

“Overconfidently conspiratorial: Conspiracy believers are dispositionally overconfident and massively overestimate how much others agree with them.” Gordon Pennycook, Jabin Binnendyk, and David Rand (PsyArXiv, April 4 2025).

This is a well-written, thought-provoking and original post. It's easy to see the impressive amount of work that went into it. Thanks.

Much food for thought here Justin as I despair about how natural stupidity will be shaped by artificial intelligence. Thanks.