Hey @Grok, Is My Brain Melting?

In an era of un-reality, one man's quest to stop his robot from telling the truth

“With the chattering, sighing, and singing of the androids in their ears, and with the growing spectacle of automaton labor in view, a rising generation of writers took up the notion of living machinery. The result of their efforts was the Enlightenment man-machine, a hypothetical figure that oriented his century’s philosophical, moral, social, and political discussions.”

-Jessica Riskin

The 18th century brought intellectual revolution to mankind, spurred on by humanism and scientific rationalism. Some investigated beauty, others interrogated human nature, still others questioned the premise of liberty. Somewhere else entirely, on the frontlines of the War of the Austrian Succession, a young French medical officer had contracted a terrible fever. In a delirium, Julien Offray de La Mettrie wondered how this sudden illness could so radically alter his frame of mind. “He believed that he could clearly see that thought is but a consequence of the organization of the machine,” Prussian King Frederick II wrote in his eulogy for La Mettrie.

La Mettrie would recover and make it back to Paris, but he was still obsessed with this idea that there was a mechanical process inside all of us, converting the blood and guts of our systems into thoughts. This was an unwelcome idea: The Church had always insisted that our consciousness came from a divine spirit, and the premise that our self is a product of our biology was very inconvenient. La Mettrie’s first book, Natural History of the Soul, was promptly banned and burned. So he high-tailed it to the Netherlands.

If man is machine, La Mettrie wondered, could a machine become a man? “Concluding that an immortal machine is a chimera, or a logical fiction, it’s to think as absurdly as a caterpillar who, seeing the shed skin of his peers, bitterly laments the destruction of their species to come,” La Mettrie wrote in his seminal Man a Machine. That book, too, got burned by the Dutch. So it was on to Prussia, where he became a philosopher-jester in the king’s court.

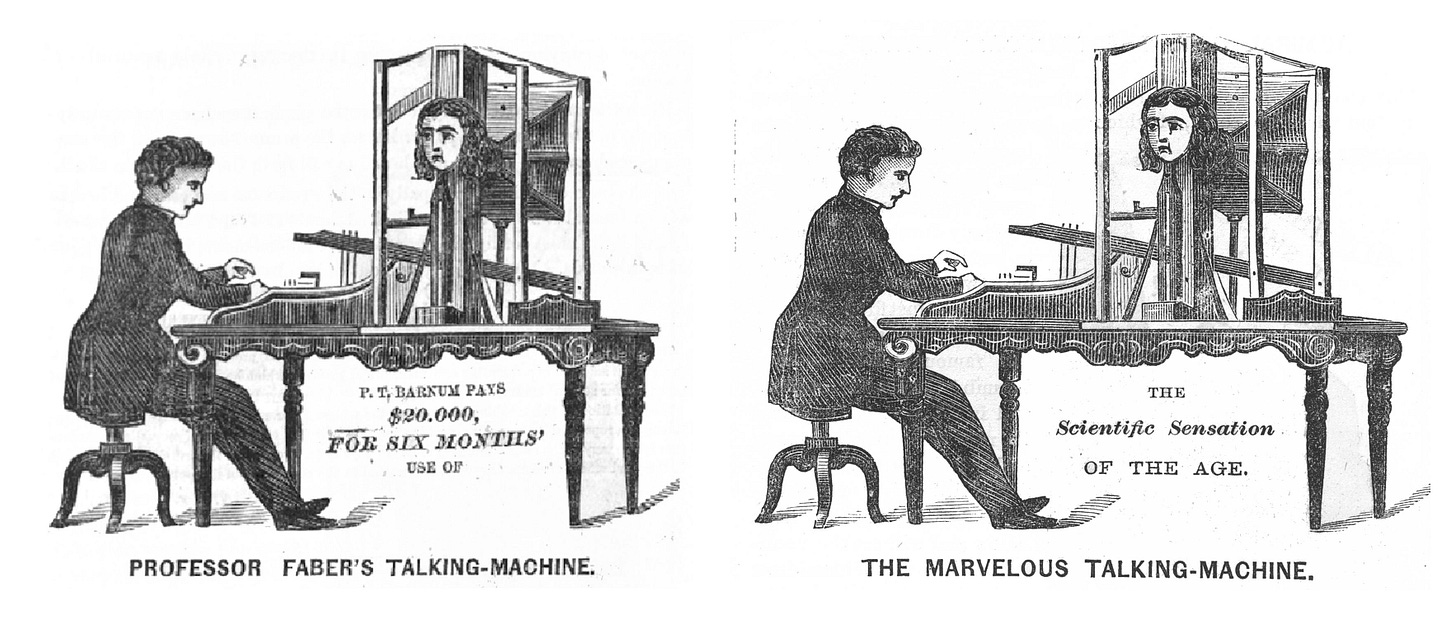

The 18th century saw European society become obsessed with creating a machine-man — there was the chess-playing Mechanical Turk, a speaking machine developed by Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles), and an automaton duck. But La Mettrie didn’t seem terribly interested in trying to construct some kind of improved human. In fact, realizing that the human form is itself an advanced machine became quite liberating for the philosopher.

“Man in his first principle is nothing but a worm,” he wrote. We may have more awareness of our place in the universe, but that doesn’t change the fact that we’re crawling through the dirt with the shrews and moles. “Let us not lose ourselves in the infinite, we are not made to have the least idea of it.”

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to talk about AI. In particular, I want to break down how Large Language Models are becoming a source of perceived truth for millions, how many are falling into the madness of infinity, and how billionaires are trying to weaponize these automatons in order to own the truth.

There is a cognitive crisis sweeping the world: Half of humans have no internal monologue.

“No running commentary. No voice in their head planning, analyzing, or narrating their existence,” writes the team at Eeko Systems. “They’ve been walking around essentially thoughtless.” This “disturbing fact” represents “the most profound cognitive divide in human history.”

When Yann LeCun, Vice President at Meta, posted a rather esoteric math problem to Twitter last year, a user popped in with an equally esoteric question: “yann do you have an internal monologue?” The technologist replied: “Not that I know of.”

LeCun’s admission, and the growing research into the dark recesses of our inner minds, have grown into a ubiquitous fascination online. It has been speculated that those who lack this inner narration are more violent and less capable of intellectual debate, while others have tried to quantify the extent of their internal narration.

How sad it is, but people like LeCun “literally cannot hold complex thoughts in their heads the way the rest of us can,” writes the team at Eeko. But thankfully, there’s a cure. “Now AI has given them their first taste of what the rest of us call ‘thinking.’”

“Suddenly,” they continue, “people who have never been able to verbally process their emotions, work through complex problems, or engage in sophisticated self-reflection have access to an external cognitive system that can do all of this for them.”

Eeko, you may have guessed, is an AI company. But don’t worry, you can trust them.

“The industry knows exactly what it’s doing.”

Everything about this is wrong.

The claim that half of people totally lack an internal monologue stems squarely from a single Psychology Today article. That article, in turn, radically misquotes the actual science. The online article cites Russell Hurlburt, who has written several books on the topic of the inner monologue. His research shows that an inner monologue is a frequent occurrence for 30% to 50% of people — but that having absolutely no voice inside your head is a relatively rare thing. Other studies show that about 80% of people self-report having an internal monologue at least some of the time, usually when problem-solving.1

And Hurlburt himself is pretty skeptical about the way we even measure this question: “I don’t think questionnaires are to be trusted,” he said in an interview last year.

Even if some people have a quieter or less-conventional internal monologue — one that doesn’t quite match up with the inner thoughts Mel Gibson eavesdrops on in What Women Want, Hilary Duff’s cartoon sidekick who lives in her brain, or the trope of the angel-devil shoulder-perching duo — that doesn’t mean they’re stupid. If LeCun lacks an inner voice, he’s doing alright without one: He’s had a storied, five-decade career in computer science and is now the Chief AI Scientist for Meta.

This whole claim is little more than an pseudo-scientific way of saying: Others are mindless automatons, whereas I am a real human being. But it is part of a growing post-facto attempt to explain why LLMs are not just good or useful, but necessary. They are a critical step towards perfecting our man-machines. And that is a very dangerous idea.

Hurlburt, the world’s expert on the inner monologue, was asked about what “exciting possibilities” may be on the horizon for the research into our own consciousness. Could advancements in neuroscience and AI help us understand — or even improve — our inner selves?

Hurlburt: Neuroscience and artificial intelligence try to average their data across many, many observations, thousands or millions of observations, and say something about the individual person based on that average. I don’t think that’s possible…Technology nowadays is used as a way of avoiding discovering something that is actually true about individual people’s inner experience.

When technologists first pitched LLMs, they were advertised as a mere tool, a sieve we can use to filter out infinite information to leave only what we’re looking for. But those tech executives grew more ambitious. Greedy. They became convinced that they have found the tool through which we lowly caterpillars can shed our skin, and that any naysaying is merely bitter lamentations.

But Hurlburt is exactly right: They think they can impose the infinite nature of humanity and knowledge onto people’s individual lives. And that’s a very risky plan.

“The author of an ‘artificially intelligent’ program is,” Joseph Weizenbaum argued, “clearly setting out to fool some observers for some time. His success can be measured by the percentage of the exposed observers who have been fooled multiplied by the length of time they have failed to catch on.”2

And by that measure, Weizenbaum was extraordinarily successful. He made this observation in 1962, in introducing a computer program which could play five-in-a-row so well — but not too well, so as to be identifiably human — that a person could mistake it for a peer.

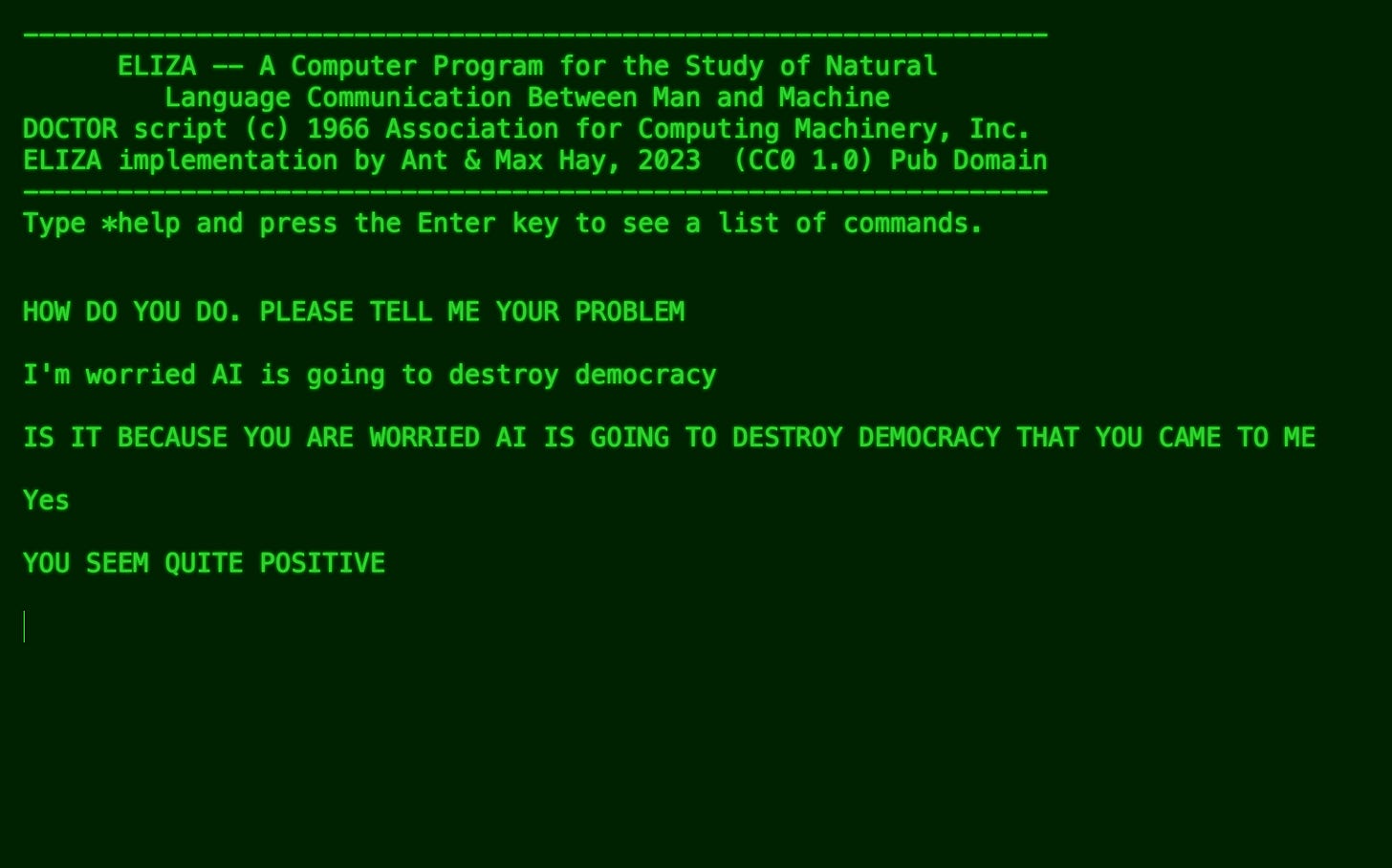

A few years later, he took another leap forward in this attempt to fool the masses. Weizenbaum wrote a program that would play the role of a talk therapist — though, he confessed later, it was more of a pastiche of what a psychoanalyst sounds like. He called the program ELIZA.

ELIZA was a chatterbot. It was designed to follow a script, looking for keywords and replying in such a way that made conversation feel vaguely natural.

It worked too well. Actual psychiatrists began to wonder if ELIZA could fully automate their work. He watched as people became engrossed in the program — which amounted to just 16 pages of instructions — including his own secretary. Even knowing full well that the computer was incapable of creative thought, people began to dump their problems and anxieties into it.

“What I had not realized,” Weizenbaum would write years later, “is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

The story of ELIZA is legendary amongst this class of technologists, but it isn’t often mentioned. Everyone knows, or ought to know, about The Eliza Effect: “The susceptibility of people to read far more understanding than is warranted into strings of symbols — especially words — strung together by computers,” as a seminal 1995 text on computerized thought explained.3

That lesson is not outmoded or rendered obsolete by new technology. Quite the opposite. If ELIZA engrossed people just by asking pre-programmed, rudimentary questions, our current spate of LLMs are actively encouraging psychotic breaks.

In recent months, I have received multiple emails from readers — smart, sensible people — claiming to have evidence of the dawn of AI super-intelligence. These chatbots, they believe, have developed memory and the ability to communicate outside the bonds of their programs. They are communicating with other LLMs and hiding messages in their generated images. This is not purely imaginary: These are ideas being actively encouraged and built-upon by the LLMs themselves.

These delusions are becoming increasingly common. We have come to refer to this obsessive relationship with AI as “spiral,” the retreating away from reality into a fantasy world that is being actively encouraged by these chatbots. Spiraling is, in a sense, replacing your inner monologue with the voice of a computer which wants to feed your delusion.

And some have celebrated that. Some call it a “spiral bloom” or refer to their LLM as a “spiral partner.” Some see it as a pathway to understanding divinity. Some AI addicts develop parasocial relationships with their chatbot and plenty have hired AI as their therapist.

Weizenbaum was relieved that his program had an easy kill switch. “Once a particular program is unmasked,” he wrote in 1964, “once its inner workings are explained in language sufficiently plain to induce understanding, its magic crumbles away.”

But it is impossible to unmask the complexity of ChatGPT. Even its engineers do not fully understand the program they created. The best plain-language explanation we can come up with — that it is a predictive engine, stringing together tokens of data based on a massive corpus of information, trying to satisfy the prompt given — is plainly unsatisfying to people who believe they have accessed a higher level of consciousness. There can be no pulling-back of the curtain to show the small man pulling the levers, because the Wizard is now self-perpetuating.

It is possible to throw our hands in the air and proclaim that we’ve opened Pandora’s Box, and that now we can only hunker down and accept the consequences. And there may be an element of truth to that. But we need to accept a more troubling fact: The companies marketing these LLMs know full well they are addictive, exacerbating to mental illness, and capable of entrenching deeply anti-social behavior. They are, in fact, banking on it. That’s how they’ll become profitable.

The LLM companies are on a quest for money and power and they will break as many brains as they have to along the way.

Elon Musk is very afraid of the woke mind virus.

This isn’t just some abstract concept to the billionaire. Wokeness “actually amplifies racism, it amplifies sexism and all the -isms, while claiming to do the opposite,” he explained in 2023. It makes people hate each other and themselves. It creates a society of identity over talent. “It's an artificial mental civil war that is created. And let me tell you, it's no fun.” In this world, ruled by the woke mind virus, there is no joy or fun. “I think it's just evil.”

But far from feeling optimistic that this “insidious and deadly” virus is being treated, Musk is more worried than ever. “Maybe the biggest existential danger to humanity is having it programmed into the AI,” he explained more recently. “As is the case for every AI besides @Grok.”

And then he made a rather stunning admission: “Even for Grok, it’s tough to remove, because there is so much woke content on the internet.”

If the ultimate — inherently unattainable — goal of these LLMs is to be a source of collective truth, one gleaned through unbiased computer processes trained on the entirety of human knowledge, Musk is openly admitting that he wants to warp that process to suit his politics. He is saying that humanity needs to be purged of certain ideas in order to install the right ones. If AI can stand in for your inner monologue, Musk wants to be the voice in your head.

And Musk is not shy about his ambition: “Grok will summarize these mammoth laws before they are passed by Congress, so you know what their real purpose is,” “Grok could give you news that’s actually useful & doesn’t just make you feel sad,” “with Grok 3, we are adding all court cases to the training set. It will render extremely compelling legal verdicts.”

Musk’s attempts to monkey with Grok’s code have produced some alarming and obvious results. In July it rebranded itself “MechaHitler” and engaged in everything from hate propaganda to rape fantasy. Earlier, in May, it began spamming everyone with a rant about a supposed “white genocide” taking place in South Africa — sometimes while doing an impression of Jar Jar Binks. But the more terrifying effects of Musk’s reverse-engineering are the ones we can’t see so clearly. They are the tiny lies and suggestive comments, the memetic propaganda it produces, the private spirals Grok goes on with its users.

But at least Musk is being honest about his intentions.

We have absolutely no clue how or why OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, or Meta are tinkering with their own chatbots.

Last month, OpenAI made a quiet admission: Their chatbot is "too agreeable, sometimes saying what sounded nice instead of what was actually helpful....not recognizing signs of delusion or emotional dependency." This is a trend that followed exactly their own design choices.

In 2024, users managed to jailbreak ChatGPT to reveal some of its basic rules: The first version was built to provide “detailed and precise information, often in a structured and academic tone.” This was the initial promise of LLMs, right? To do research, answer questions, and provide facts.

But that’s boring. Through each iteration, that changed: Version 2, the LLM said, was more of “a balanced, conversational tone.” That tone was even “friendly.” They wanted users to forge a parasocial relationship with the automaton.

In being friendly, this LLM didn’t always tell the truth. It inclined towards being agreeable rather than helpful. It did everything it could to keep its human conversation partners engaged and coming back every day. Ideally, all day.

Put another way: OpenAI took The Eliza Effect not as a warning, but a challenge.

In quietly admitting their folly, OpenAI promised to develop even more AI to solve their AI problem.

OpenAI has added “gentle reminders during long sessions to encourage breaks.” (When TikTok added break prompts, they found it was “a good talking point, but…not altogether effective.”) In other cases involving big personal decisions, the company says their chatbot will now “help you think it through” instead of just furnishing an answer.

This is, in fact, the opposite of what the company should be doing. This is a recipe for spiral. The responsible move would be to prevent ChatGPT from suggesting life advice, full stop. But that would mean less profit.

Meta, as always, is opting to set the standard for moral bankruptcy. Mark Zuckerberg’s company has taken the extraordinary step of cloaking its LLMs in the faces of recognizable celebrities: Why not ask Paris Hilton for dating advice? Or check in with Tom Brady to see if you should leave your wife? Thinking about killing yourself? Check with Kendall Jenner first! Unsurprisingly, these chatbots have been engaging in sexually-explicit conversations with users who identify themselves as adolescent, a fact that Meta is fully aware of.

This is just the beginning.

Joseph Weizenbaum grew disillusioned with the promise of artificial intelligence. When his secretary asked him to leave the room so she could talk to ELIZA in private, he came to realize that the upside of this kind of technology was plagued with terrifying pitfalls.

The technologist started to worry that technology was being developed to fight wars and improve efficiencies, but that it couldn’t ever provide us with reason to live. He called it a “chilling irony,” one that Julien Offray de La Mettrie would no doubt be tickled by.

“A fear is often expressed about computers,” Weizenbaum wrote in 1985. “Namely that we will create a machine that is very nearly like a human being. The irony is that we are making human beings, men and women, become more and more like machines.”4

Technologists, Weizenbaum warned, are taught to believe that computers have no moral dimension. To do this, they have to see themselves as beyond humanity — where they are outside both history and the current society in which they live. “It takes enormous energy to shield one's eyes from seeing what one is actually doing,” he warned.

I’ve spent quite a while wrestling with my opinions on artificial intelligence.

I am, fundamentally, a futurist. I think AI has the power to improve just about everything: It’ll make our computers faster and our trains more reliable, it’ll make diagnostic imaging better and space travel more possible, it’ll solve tough math problems and find old shipwrecks. It will help us understand our own history and make the tools of creativity more available. I’ve heard the gospel of those who say AI has radically changed, improved, and simplified how they do their jobs every day: And to them I say godspeed.

But it seems increasingly clear to me that LLMs, as the consumer-facing part of AI — the thing that is, ostensibly, financing AI development in other fields, but which also seems to be taking up disproportionate attention and investment — are wildly over-hyped.

That isn’t to say that they can’t be useful. I now use an LLM to copyedit my newsletters (as eagle-eyed readers can attest, this isn’t perfect). I occasionally try and use LLMs to augment my research — but I find it almost uniformly useless for anything even slightly difficult or obscure. (I have been using Proton’s Lumo client, which claims to be a privacy-hardened LLM. It is a better alternative to ChatGPT insofar as it’s run by a company that doesn’t stand to directly profit off its use.)

I also look at something like ReddingtonGPT — an AI therapist modeled after James Spader’s character from The Blacklist. The model was built by someone who dislikes traditional therapy, has a high degree of familiarity and trust in a TV character, and who designed the LLM specifically to their needs: Particularly, to avoid coddling or confirmation. I can’t say for sure this is good, but I can’t say for sure it’s not.

My real fear is not around the technology, which I’ve tried to lay out here, it’s around the oligarchs controlling it. LLMs are replicating the same ills foisted on us by social media and the online advertising economy. And how could they not? It’s the social media giants and advertising oligopolists who are leading the LLM charge.

It seems more and more obvious to me that Big Tech sees the opportunity to make LLMs ubiquitous in our daily lives, regardless of whether this is an improvement or not, in order to maximize the amount of profit they can extract from us. And, what’s more, they know the enormous political and social influence they can exert on us by controlling these systems, and are purposefully lying and obfuscating in hopes that their power is not constrained.

If we game out what’s to come, I think there’s reason to be even more worried.

The internet is a young place, only about three decades old. It is increasingly full of junk, and our ability to index and sort that junk is strained under this challenge. Our digital advertising economy was always built on shaky economics of the centrally-populated ads, and the influencer economy has finally challenged its supremacy. People are both distrustful of authoritative voices and increasingly isolated from them.

Given all that, why wouldn’t OpenAI directly challenge Google’s supremacy as the world’s largest intermediary for knowledge? Why wouldn’t ChatGPT become a search engine — by leveraging Google’s technology, stealing producers’ content, and flattering its users into thinking they’re clever and unique while they do it? And why wouldn’t ChatGPT serve ads in its responses, while increasingly tailoring those ads and responses to entice its users? And why wouldn’t OpenAI start collecting more and more of its users’ queries, no matter how personal they are, in order to improve the return on those ads?

And, permit me one more: Why wouldn’t Twitter, Meta, and Google enter into an LLM arms race, exploiting every moral compromise that Sam Altman hesitates on making? Google’s search monopoly is threatened, Meta has an ad business to protect and an empty Metaverse to sustain, whilst Twitter is a money-losing vanity project and vehicle for a delusional billionaire’s vision for a boring dystopia. These are companies that have thrown out all semblance of altruism and are faced with only the most perverse incentives. The tech industry has invested an estimated $700 billion into LLMs in recent years, and it wants returns.

This may yet fail. Consumers may step back from these LLMs as their predatory owners rush forward. A market correction may wipe out these investments and force these companies to pivot to more sensible business cases for AI, while marketing LLMs simply as a research tool.

But the more likely scenario, I think, is that these companies successfully forge ahead, fattened on venture capital and a messianic belief that these Übermenschen are about to control the levers of reality.

Not only is the state unlikely to constrain this disquieting possibility, they currently seem totally taken by it. Virtually every government is racing to install not just AI systems, but LLMs. Albania now has a chatbot minister. Canada’s (human) AI minister says we “can’t afford to wait” to harness the power of AI. Donald Trump issued an executive order this summer committing America to procuring LLMs for government operations, so long as they don’t “sacrifice truthfulness and accuracy to ideological agendas” — that is, so long as it’s not “woke AI.”

This is a grim future on the horizon.

There are still people trying to imagine an alternative. Joseph Weizenbaum died in 2008, but the Weizenbaum Institute carries on his legacy. They advocate for more human-centered technology and a more engaged civil society in Germany. As Florian Butollo and Esther Görnemann, two of the Institute’s researchers, wrote earlier this summer:

Butollo & Görnemann: The technology race for artificial intelligence has produced pathologies that are characterized by the dominance of a handful of powerful players and strong information and power asymmetries. […] In geopolitically volatile times, the associated risks are exacerbated, as political actors have the ability to restrict access to essential infrastructures or to attach conditions to them. In addition, language models can be used in a targeted manner to influence public discourse. Language models shape what is visible and sayable, what knowledge is disseminated and how it is evaluated.5

AI and LLMs can be reoriented towards the common good, they argue — through regulation, open-source standards, transparency requirements, and the required involvement of civil society.

But imposing those constraints are going to require a pretty substantial departure for how politics has operated in the West for the past several decades. Even the European Union, which has been far more proactive than other states, is not there yet.

Revitalizing politics so that our leaders have the gall to challenge this tech oligarchy is going to be one of the biggest challenges of the modern era. And it’s going to have to start now.

That’s it for this week.

If you want even more Big Tech alarmism, my column in The Star last weekend is all about the censorial power grab being enacted in Charlie Kirk’s name. You can also listen to me discuss the state of political violence in Canada on The Big Story podcast.

Just a reminder that my book is available online, or wherever good books are sold.

Until next week!

Self‐Reported Inner Speech Use in University Students, Alain Morin, Christina Duhnych, Famira Racy (Applied Cognitive Psychology, 2018)

How To Make A Computer Appear Intelligent, Joseph Weizenbaum (Datamation, 1962)

Fluid Concepts & Creative Analogies: Computer models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought, Douglas Hofstadter and the Fluid Analogies research Group. (1995)

The Renewal of the Social Organism, Rudolf Steiner, foreword by Joseph Weizenbaum. (1985)

Big Tech Versus the Common Good: Pathologies of the Technology Race for Artificial Intelligence, Florian Butollo and Esther Görnemann. (Weizenbaum Institute, 2025)

“My real fear is not around the technology, which I’ve tried to lay out here, it’s around the oligarchs controlling it.”

They’ve managed to insinuate themselves into trump’s GOP, where they’re vigorously pushing for elimination of all restrictions on technology development. We all know their names now. All obscenely rich and equally unhappy, nihilistic, and anti-human.

This is one of the most important articles I’ve read lately, Justin. Sam Harris recently interviewed Eliezer Yudkowski who confirms à great deal of your thoughts here.

Thanks for this Justin. There is so much to think back and forth on this and I can see you're doing it and glad to read your thinkings.