The Deportation Comedy Hour

How humor masks inhumanity

The house lights dim. The stage lights go up.

Upstage are neat rows of seats and desks, made to look like a parliamentary chamber. In one sits, we presume, a politician — played by a kid, perhaps only just out of his teens. He wears an oversized suit and droops out of his chair, snoring. Suddenly, on his desk, an alarm clock goes off and he jolts awake.

The audience laughs.

Another kid-politico stands up at his desk, furiously sticking out his finger to deliver an attack on his political opposites: But he stutters and stammers so badly he can barely eke out a sentence.

The audience keeps laughing.

Another junior politico rushes in and sits in his chair, but drowns out the debate with his incredible flatulence.

The audience is in stitches.

The stage lights dim, the players exit. The stage lights come up again, the players do their Heil Hitler salute, bow, return backstage.

The Hitler Youth put on these popular evenings of entertainment in the dying days of the Weimar Republic, as Germany’s valiant effort at democracy was murdered by institutional dysfunction and far-right militancy. While the intelligentsia and bon vivants enjoyed comedy and art at Berlin’s many cabarets, the Hitler Youth were subverting expectations by putting on their own form of satirical salons.1

It is easy, perhaps comforting, to think of inter-war Germany as a place where comedy was going as fascism was coming. To imagine that the rise of Adolf Hitler came with a dark pall that choked out all good humor. It is just one of the ways in which we transpose the final years of Nazi Germany’s genocidal history onto the very beginning of its existence.

But this is, of course, a mistake. The machinery of Hitler’s terror took years to build. It took millions of laborers to assemble it. And it was a process that liberally used laughter and comedy to distract the public as it was built.

America is now governed by a lawless regime which has bestowed upon itself the right to arbitrarily surveil, seize, detain, abduct, and imprison people — including American citizens. And it is spewing out memes as it does.

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless: An uncomfortable parallel.

Since taking office, Donald Trump has deported at least 100,000 people. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has hit its target of making 2,000 arrests daily: And is now ramping up to increase that target to 3,000 per day.

These are not orderly, normal deportations — the kind where the migrant is afforded due process, where their case is reviewed to ensure that they do not face mortal danger if sent home, when their situation is reviewed one final time to see if such a deportation would be in the public interest. That is, these deportations are illegal.

To make the arrests, ICE has become an omnipresent goon squad, crashing into communities to seize people off the street, from their homes or workplaces.

Some of those targeted and arrested are, indeed, criminals — who had been tried, convicted, and who disappeared before they could be deported. But many, perhaps most, have no criminal record whatsoever: Their only ‘crime’ is being undocumented. Still others have been in America legally under a work or study permit, but their status was suddenly and arbitrarily revoked as punishment for saying the wrong thing or coming from the wrong country. Still others are American citizens or permanent residents, rolled up because they are the wrong race. ICE, and collaborators in local law enforcement and other federal agencies, have also begun rounding up anyone who resists this illegal scheme.

In recent days, President Trump has dispatched the national guards and marines to put down protests and provide muscle for ICE’s extraordinary renditions.

ICE and the Department of Justice have moved these migrants across the country, refusing to bring them before an actual court to review their arrest and deportation. They have warehoused these migrants into miserable detention facilities, particularly for-profit private prisons. They have loaded these human beings onto flights destined for places both perplexing and dangerous.

Thousands of migrants have been sent, some on military planes, to Honduras, India, Mali, Mauritania, and El Salvador.

Those sent to El Salvador, in particular, face abhorrent conditions in mega-prisons including, per Human Rights Watch, “torture, ill-treatment, incommunicado detention, severe violations of due process and inhumane conditions, such as lack of access to adequate healthcare and food.” Others are being held in a shipping container in Djibouti. These are modern gulags.

This whole process has been run to frustrate any effort by the courts to enforce the law. In recent months, the U.S. government has repeatedly slow-walked and defied court orders, practically challenging the courts to find the government in contempt.

James Boasberg, chief judge for the District Court for the District of Columbia, likened this ordeal to Franz Kafka’s The Trial.2 In the opening of the book, Josef K. awakens to find two men at his door, there to arrest him. A bewildered and nervous K. proceeds to produce his papers and insist that the two men produce their own arrest warrant.

The goons’ mysterious department “is attracted by guilt,” they insist, “as the Law states.”

“I don’t know that law,” K responds. “It probably exists only in your heads.”

One of the goons replies: “You’ll feel it eventually.”

Migrants in America find themselves in a Kafkaesque nightmare: A world where the law is arbitrary, opaque, indifferent, and cruel. But the country, as a whole, is facing an even more terrifying reality: The government has been captured by radicals who want to use these deportations to break the entire system of checks and balances.

And they’re laughing while doing it.

The study of comedy in the Third Reich basically falls into two camps: One looks at the Nazi’s use of satire before they seized power; the other looks at the criminalization of comedy after Hitler became Führer

That first area of study is radically under-appreciated. Severe and self-serious as they may be, the Nazis made aggressive use of humor in order to both solidify their movement and reach curious Germans.

Official party organs, such as Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels’ own newspaper Der Angriff, were rife with caricatures, comics, and comedies assailing their enemies — Jews, of course, but also Weimar officials, local police, leftists and moderates of all stripe.

“From the propagandist point of view, those defamatory caricatures were successful, because they caused a stir,” writes Patrick Merziger, a scholar who studies comedy in Nazi Germany.3 This satire helped to ridicule, minimize, otherize, and annihilate the humanity of the Nazi’s opponents. When those in power launched legal action against the Nazis, it only further entrenched the us vs. them narrative being developed by Goebbels.

While much of this content was for Nazi diehards, they also produced satire for the masses. O diese Nazis! (literally: Oh these Nazis!) was meant to find a more general audience. In the play, the flawed protagonist is a bumbling-yet-particular bureaucrat who finds himself frequently trying to apply the law to the sympathetic and brave Nazis. By the end, the main character announces a sudden reversal and declares himself a National Socialist.

That second era of humor in Nazi Germany is more broadly understood as the verboten nature of comedy. But this whole idea is based on a myth.

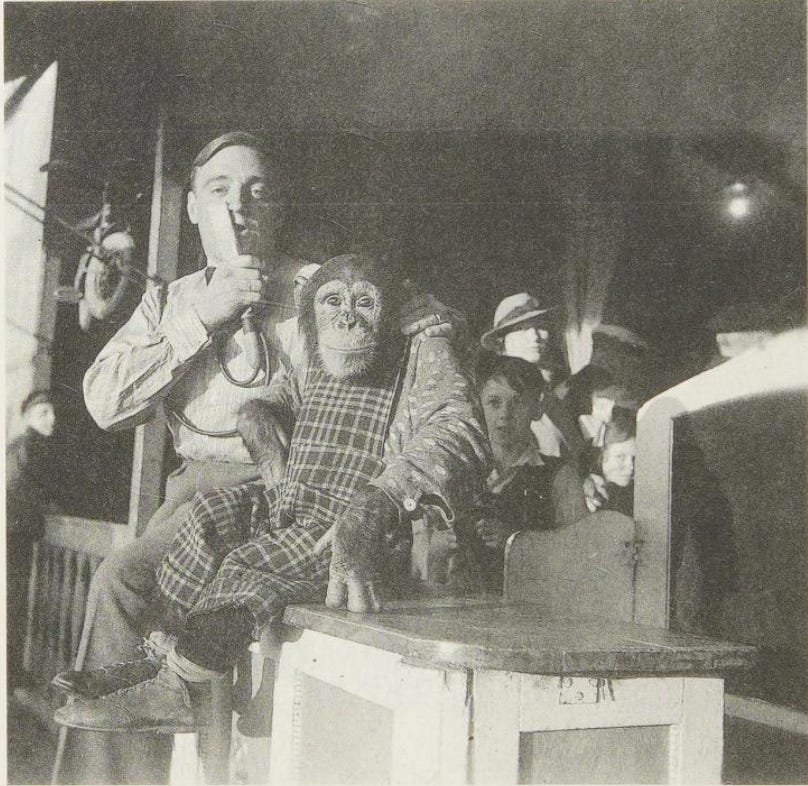

There’s obviously some truth to it. Just take Fritz Peter4, who sought to mock the uniform reverence that German citizens were required to show Nazi officials. Peter taught his pet chimpanzee to perform the Hitler salute to any person in uniform — be they a mailman or the Führer himself. The nascent National Socialist government issued a directive forbidding any animal from performing the flat-palm greeting, lest they be put down.

“When it came to expressions of respect for their leader,” historian Rudolph Herzog writes, “the Nazis did not have much sense of humor.”

If you know anything about humor in Nazi Germany, you might know of the phenomenon of the “whispered joke” — the quiet resistance which targeted the regime through quiet, cutting humor aimed at the Nazis. This notion suggests that the edict against comedy was so severe that one must deliver a punchline in hushed tones.

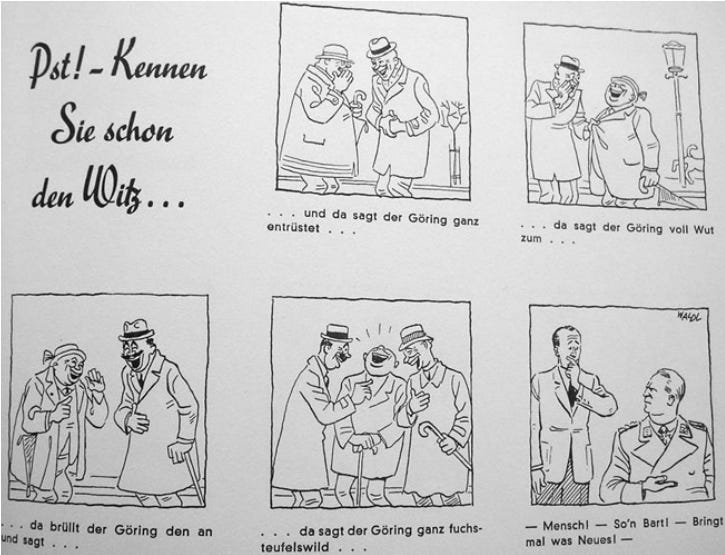

But this is where things start to fall apart in this narrative. There is ample evidence that Nazi propagandists welcomed these jokes, because they were often so innocuous so as to give the illusion of freedom of expression. A comic strip in a pro-Nazi newspaper even depicts two German citizens cracking jokes about Hermann Göring, one of the most powerful men in the Nazi Party, and his temper. In the last panel, Göring hears the jokes and exclaims: “My god, that’s an old one! Come up with something new!”

The fact is, the state did allow some comedy, within limits. and it continued to try and use satire to both distract from and build support for its seizing of the levers of power.

In the early days of the regime, the Nazis continued to pump out comics, plays, and even radio comedies meant to satirize their enemies. But, as Merziger argues, this work ranged from limp to actively offensive to the German people, who felt as though they were being laughed at.

“Satire was now published in an environment where exclusion and annihilation were no mere metaphors but real political and social processes,” Merziger writes. “In this context, satire’s metaphorical ‘annihilation’ of the opponent was less impressive.”

The Nazis were shifting, he argues, and it wasn’t as simple as a new edict against jokes.

The idea of satire, used so effectively by the Nazis against the Weimar Republic, made the public nervous. It made them fearful that they, too, would be targeted: Because they were weak, poor, illiterate, brown-eyed, or otherwise anything less than the Aryan ideal of a German citizen. “To be shut out of the Volksgemeinschaft [national community] meant total exclusion,” Merziger writes. They had watched that exclusion happen to the Jews, Roma, homosexuals, and now they feared it could target them. But the public still wanted entertainment. This “demanded a change of form, away from somehow irritating jokes and away from destructive satire to a new form which allowed humour that could bring people together.”5

“Satire did not disappear because politicians or institutions wanted it gone; ideologues, rather, supported it,” Merziger writes. “The demise of satire was due to the audience’s dislike, and institutions fell in step.”

Merziger has argued, for years, that there is a third trend in comedy under the Third Reich: “Deutscher Humor,” or German humor.“

This would produce a kind of comedy that continued to vilify the other in German society — homosexuals and Jews, primarily — while painting Germans, even the lazy and boorish, as heroic. The rules of German comedy would become clear.

And the prime example comes in the 1939 film Robert und Bertram, released just two months after Kristallnacht and two months before the outbreak of WWII. The film, a musical romp, tells the tale of two loveable scamps who travel throughout Germany, robbing rich Jews to help out the downtrodden.

“You see, Robert,” Bertram tells his compatriot at one point, “you are a washed-up genius, and I am a drop-out bourgeois, one who would rather be a tramp than a conformist.”

Their behavior — rebellious, mischievous, occasionally criminal — ran afoul of everything the Nazis demanded of the German citizenry. It is all rationalized, though, because the pair are striking at the heart of theft and corruption inside the German state. “After all, normal standards only apply when it is a question of normal circumstances,” one German reviewer wrote at the time.

There is still that satire at the core of the story: A Jewish banker, made to look alien and otherworldy, is heartless, greedy, and eventually revealed to be a criminal himself. But the Germans are all protected from ridicule, be they noble blond-haired officers or lazy petty thieves.

This Robin Hood treatment, German professor Mary-Elizabeth O'Brien writes, betrays the real ideological purpose behind the film. “The ‘higher’ moral propagated here is that the theft of Jewish property is not really theft at all. Since the Jews are themselves exposed as thieves, expropriating their assets is a just and socially acceptable action.”6

In the film, Robert and Bertram are eventually arrested and sentenced for their antics. But they stare out of the bars of a cell with joy, believing in the wisdom of “Arbeit macht frei” — work sets you free, the inscription set into the gates above the entrance to Dachau. The symbolism becomes even more bizarre when, despite being still alive, Robert and Bertram ascend to the afterlife, where the gates of heaven slam shut behind them.

In our overly-simplistic understanding of Nazi Germany — the one where laughter is criminalized, where Hitler’s rhetorical prowess radicalizes the entire German public long before the war begins, where the public accepts the mass deportation of Jews without question — we fail to appreciate the role of propaganda like Robert und Bertram in conditioning the public. As a German reviewer wrote upon the film’s release: “For the first time ever in a film Jewry becomes the target of a convincingly effective ridicule.” Another noted that the source text, written nearly a century earlier, “foresaw therein our own violent reckoning a hundred years later with all those who put self-interest before the common good.”

The official marketing material encouraged cinemas to highlight the movie as “Schadenfreude in its most harmless form.”

If the Nazis had used satire as a weapon to seize power, they were now using a softer form of satire to tell the German people comforting myths about themselves. This kind of comedy wasn’t meant to challenge, like real satire does, but to dehumanize the internal enemy and comfort the masses.

Film historian Klaus Kreimeier has called the film an "advertisement for death." He argues that, just as the Nazis were crushing all local opposition to their increasingly-tyrannical rule, this “refreshing bath” of Schadenfreude, as the reviews called it, had served a very clear purpose.

Kreimeier: The fact that by 1942 this genre had run its course can be attributed to the fact that the killing machinery was running at full speed. Propaganda had done its job. The Nazi leadership had to have assumed that the mass deportations would not go unnoticed by the general populace, and the mass exterminations were probably a public secret. But thanks to factors that included a series of several very successful films, the German people had been psychologically prepared. That, in any case, was how the political leadership and their minions in the film industry saw the situation.7

Herzog agrees, seeing the effective replacement of genuine comedy — which challenges power, mocks social rigidity, and reflects the shifting positions of the body politic — with regimented state-approved entertainment as a "coolly planned, larger strategy.”

“A seemingly harmless comedy was a far more effective means of infusing poisonous propaganda than the weekly newsreels,” Herzog writes. “Audiences laughed and did not expect any political message. But the humor in question made them receptive to the campaigns that led to the persecution, ostracism, and extermination of Jews.”

Earlier this week, Derek Guy posted his origin story: How his parents fled Vietnam after the Tet Offensive and settled in Canada, where he was born. His parents worked whatever jobs they could find and, soon enough, emigrated to the United States — and overstayed their visas.

“Since I came here without legal documentation,” Guy writes, “I eventually fell into the category of being an undocumented immigrant.” In the decades since, Guy has become an internationally-known style writer — known online as "the menswear guy” — but he remains undocumented.

“I think the ICE sweeps are inhumane,” he continued. “I support and admire the protestors who are putting their bodies on the line for non-violent resistance.”

When Guy tweeted this to his 1.3 million followers, many held up Guy’s story as a sterling example of the regular, even extraordinary, people who Trump is desperate to deport. Sending people like Guy “back” to their home countries — places where they haven’t lived in decades, if ever — would be absurd and cruel.

And yet scores more replied to Guy’s post with a clear, unambiguous message: The cruelty is the point.

When someone suggested to Vice President JD Vance that Guy should be arrested and deported, he responded with a GIF of Jack Nicholson nodding creepily. When someone tagged the Department of Homeland Security, their official account replied with a Spy Kids GIF.

A well-liked writer delivered a thoughtful and personal story of his own experience with immigration status, blowing a hole in the oft-repeated mantra that “illegal” immigrants are dangerous criminals. And the state responded by annihilating his humanity with bitchy little GIFs.

The use of AI to rapidly generate these satire is only further creating this unreal space. Turning this into a joke — oh, there’s Trump as the Pope. There’s Trump waving migrants goodbye from a McDonald’s drive-thru window. There’s an ICE agent as a Studio Ghibli character. — makes the stakes feel lower and less real. It permits Trump’s cultish defenders to laugh instead of grit their teeth. It obliterates the humanity of migrants and minimizes them the ephemeral.

The state, as it bemoans often, no longer controls the tools of culture. It cannot push out propaganda films — at least not ones that any real people will watch. But, thanks to services like ChatGPT and Grok, it can now quickly draw that refreshing bath with ease.

There’s no doubt that these memes are not going to convince anyone. They are grotesque and crude. But they do cause a stir. And they redicule all legitimate criticisms of this mounting centralization of power, all while deluding working-class Americans into thinking these developments are good for them.

So migrants become simultaneously an existential threat, a foreign invading force intent on committing violent crime, at a minimum; and, at most, destroying the country from the inside. But, at the same time, they are cartoonishly pathetic figures, and the sound of the chains clanking around their feet makes for great ASMR.

Comparisons between the modern and Nazi Germany are always fraught. It is easy to write off any similarities by noting that our current state doesn’t resemble the end point of Nazi terror. Which is certainly true.

But there was a decade between even Hitler’s first push for power, in 1923, and the abolition of democracy. And five more years after that until Kristallnacht. All along that process, the Nazi Party innovated new ways of polarizing, dehumanizing, de-legitimating, satirizing, propagandizing, and caricaturizing their own criminal activity. Efforts to resist were painted, successfully, as extremism and lawlessness. By the time the extent of the power grab had become clear, it was too late to resist.

We think of ourselves as smarter, more moral, more literate than the German public back then. But we’re not. We are just as susceptible to flattery, deception, manipulation. Even if this state does not arrive at the same genocidal endpoint as Nazi Germany, it is increasingly inescapable that they are employing the same tactics that allowed for total state control.

As Tim Walz remarked, astutely, earlier today: “The road to authoritarianism is filled with people telling you you are overreacting.”

That’s it for this week.

Apologies for the radio silence over the past month: The election flowed right into my trip to Taiwan, which was followed by jet lag, looming deadlines, and some other projects.

But rest assured the train is back on the tracks.

On Sunday I’m off to Kastanakis, Alberta, for the G7 summit. Expect a quick dispatch from there about whatever chaos ensues. Then, I’ve got some interesting observations from Taiwan.

From elsewhere: I’ve got a breakdown of Canada’s new defense spending commitments in The Star, an investigation into Ottawa’s ailing tech infrastructure in The Walrus, then I’ll have some insights from Taipei in Foreign Policy in the near future.

Until next time.

Dead funny: humor in Hitler’s Germany. Ruolph Herzog (2011)

J.G.G. v. TRUMP, 1:25-cv-00766, (D.D.C.)

The Politics of Humour: Laughter, Inclusion and Exclusion in the Twentieth Century. Martina Kessel and Patrick Merziger. (University of Toronto Press, 2011.)

The caption in Herzog’s reads “Fritz Peter taught his chimpanzee to do the Hitler salute.” In the book itself, however, Herzog refers to him only as a “performer from Paderborn.” Confusingly, film director Fritz Lang also has a famous (albeit fake) chimpanzee named Peter. I haven't been able to solve the mystery of who, exactly, had the zeig heil monkey.

Humour in Nazi Germany: Resistance and Propaganda? The Popular Desire for an All-Embracing Laughter. Patrick Merziger. (International Review of Social Histories, vol. 52, no. S15, pp. 275–290, Dec. 2007)

Nazi Cinema as Enchantment: The Politics of Entertainment in the Third Reich, Mary-Elizabeth O'Brien. (2004)

Antisemitismus im nationalsozialistischen Film, Klaus Kreimeier (1995)

Back in the seventies Frank Zappa was warning us about American Nazis and his CNN appearance on Crossfire in the '80s warning about fascist theocracy seemed way over the top at the time but he was bang on.

https://youtu.be/B9856_xv8gc?si=rq2wtTS4IwSzmS6C

The effort to make Nazism look normal went well beyond the use of satire or humor. Neal Ascherson has an interesting review in the New York Review of Books of March 27 of eminent Nazi historian Richard Evans' "Hitler's People: The Faces of the Third Reich." Hitler's helpers were ordinary Germans who "had been brought up in the culture of rancid, self-pitying national paranoia after the defeat of 1918." Like MAGA fanatics today (an estimated 20% of the American population), who insist that America is broken, they abandoned critical reasoning.