The Eye That Never Sleeps

Social media is making us afraid and anti-social. What if that's the point?

On May 4, 1886, someone in Chicago’s Haymarket Square threw a stick of dynamite at a phalanx of advancing police officers.

In the preceding days, the Chicago cops had shot and killed two workers, striking for an eight-hour work day. Undeterred, the laborers congregated defiantly in the square for an entirely peaceful demonstration. Then the police arrived to break it up.

The bomb killed one policeman initially, but the ensuing gun battle left more than 10 dead on both sides. The city didn’t hesitate to identify a culprit. For months, militant labor activists with the Industrial Workers of the World — the Wobblies — had preached about the equalizing power of dynamite. A year earlier, founding member of the IWW and noted anarchist Lucy Parsons wrote a love letter to the explosive in a Chicago labor newspaper. “Dynamite,” she wrote, “its voices the only voice that oppressors of the people can understand.” A single stick of dynamite can provoke terror, she went on, and “the ‘terror’ becomes a great educator and agitator.” That was all the proof the city needed.

But they needed necks to hang. So the city turned to the famous Pinkerton Detective Agency.

So, too, did Charles Siringo, a renowned cowboy detective. He had recently given up chasing cattle rustlers like Billy the Kid and made his way to Chicago. After watching the carnage in the square, he walked into the Pinkerton offices and offered his services. “I wanted to help stamp out this great Anarchist curse,” Siringo wrote years later.1

What he found in the Pinkerton offices, however, were detectives with few scruples. They would infiltrate the Wobblies’ offices and meetings, sitting in on their debates and strategy sessions, then return to write reports full of lies and outlandish mischaracterizations. The Pinkerton agency had a narrative, and it made the facts fit.

The cops, with the help of the Pinkertons, would eventually round up eight men. Siringo sat through their trial, ostensibly to prevent jury tampering — but he was quietly confident that the jury had already been rigged, and that witnesses were perjuring themselves to boot.

All eight were convicted — including Lucy Parsons’ husband, Albert. Two men asked for, and received clemency; one committed suicide in his cell; and the remaining four were hanged for their alleged crimes.

The bombing and ensuing media frenzy spurred a moral panic over the threat of these anarchists, socialists, and activists. And that paranoia was great business for the Pinkertons and a growing industry of similar agencies — often more concerned with breaking strikes and disrupting organized labor than with solving actual crimes. These “gunmen of industry” would keep up their work so long as capital feared labor.

As this happened, Siringo rose to become one of the most revered detectives in the world. He was no fan of anarchy, but he was sympathetic to the plight of labor. And he grew more and more convinced that Pinkerton wasn’t fighting crime, it was helping to create it.

Pinkerton detectives would lie, even frame suspects in complicity to murder, because “these flashy reports suited the agency and pleased the clients,” Siringo wrote.

Siringo would spend more than two decades in the employ of the Pinkertons, trying to do good work in an agency otherwise mired in perjury and corruption. At the end of it, he published a book of his time there: Two Evil Isms. That is: Anarchism, and Pinkertonism.

“No doubt some of these anarchists deserved hanging,” Siringo wrote in his book, “but for the life of me, I could not see the justice of the conviction.” It was a case, he wrote, “of ‘money making the mare go’ with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency using the whip.”

In his book Inventing the Pinkertons, historian S. Paul O’Hara picks up Siringo’s warnings and concludes that, behind all the lore, the Pinkerton Agency was really a master of propaganda.

O’Hara: The Pinkerton eye, emblazoned with the promise “we never sleep” and evoking the political vigilance of the prewar “Wide Awake” militias, was more than a threat of surveillance; it was the company brand. Industrialists in the immediate postwar period worried about the need for discipline and the potential for crime. Allan Pinkerton built his agency into a powerful and lucrative business by exploiting these perceptions of disorder. […] Through a series of books chronicling the adventures of his detectives, he tied his reputation directly to the emerging literary genre of detective novels. Such stories guided readers through the modern world because they promised that crime was an abnormality that could be contained and that the power to place the world in order (a power held by the detective) always proved stronger than the criminal’s power to disrupt social order.2

The Pinkerton agency began as a weird externality of a society in flux. America was rapidly becoming richer, more industrialized, more centralized, more internationalist — and its still nascent system of government did not have a lot of great answers for how to handle that. First they policed the bandits of the wild west, then rose to battle the foreign-influenced anarchists looking for socialist revolution.

Through their exploits in film, on the radio, and in comic books, the Pinkertons became a product and a way to see the world.

But the real organization had become as criminal as the anarchists. The agency bilked cities for work not done (and the detectives defrauded their employer in turn.) Their rapid expansion meant hiring thugs: Relations in the Denver office got so bad one detective kept his hand on his sidearm, worried he might be ambushed by his coworkers when he showed up for work every morning.

Worse than that, the detective agency spread like mushrooms. Pinkerton franchised at first, but lost control quickly thereafter. Every town was lousy with detective agencies, legitimate and otherwise. Some did only strike-breaking, some genuinely solved crimes, some were just wannabes.

The detective industry needed paranoia to give its detectives work, so it sold paranoia too.

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to talk about how social media is distorting our perception of reality. It is making us afraid. It makes us view our own communities with suspicion and distrust, at a time where we desperately need more social cohesion.

We’ve been here before. We’ve turned fear into a profit motive, then hired the fear-mongers to keep us safe. But we’ve also woken up to that fact, and run them out of town on a rail.

We can do that again.

In September, Fox News aired a truly unhinged two-and-a-half-minute item covering protests against ICE in Portland.

The package came amid a deluge of social media video purporting to show the West coast city engulfed in chaos. Social media users insisted these anarchists were “out of control without consequences.” Antifa was “mobbing reporters and assaulting civilians.” There were “TERRORIST activities” and “thugs” who launched “projectiles” at federal agents. The protesters were equipped with riot gear and prepared to go to war, social media users said.

Few, if any, of those promoting these videos were actually there, and they all seemed to have a particular interest in pumping up the supposed threat of these protesters.

But Fox echoed this growing narrative of Portland as the epicenter of chaos. The protesters were there to “wreak havoc” on Portland, the network said. It spoke to residents who testified to the tumult. It showed graphic footage of the conflict in the streets. It caught President Donald Trump’s attention.

“What they’ve done to that place, it’s like living in hell,” he wrote on Truth Social.

On September 27, Trump declared on Truth Social that he was sending the National Guard to “war ravaged Portland.” This would be to put down “Antifa, and other domestic terrorists.” He went further: “I am also authorizing Full Force, if necessary.” (And signed off with the obligatory “thank you for your attention to this matter!”)

And then, the whole narrative began to unravel.

Local news began reporting on how ICE officers and other federal agents — who had been dispatched to Portland since earlier that Summer — had been instigating a significant chunk of the violence occurring on the streets.

When a senior Portland police officer was called to testify about the state of the anti-ICE protests, he said it was the federal officers — not the protesters — who had been “night after night, actually instigating and causing some of the ruckus that’s occurring down there.”

Other videos — ones less inclined to go viral on Twitter and the other platforms where Trump and his cohort get their news — show federal officers pepper spraying random people and firing projectiles at journalists and other peaceful protesters.

As an appeals court would later note, “there had not been a single incident of protesters’ disrupting the execution of the laws” for fully two weeks prior to Trump’s post. One report from a Portland police officer noted that, the day before his irate post, “we observed approximately 8-15 people at any given time out front of ICE. Mostly sitting in lawn chairs and walking around.”

How could there be such a chasm between what Trump saw on TV and what users experienced on social media, and what was really happening?

ProPublica helped answer that question earlier this month. They analyzed each shot in that Fox News report. It turns out the network had spliced together five-year-old footage to make Portland look more chaotic than it truly was. When the investigative outlet looked at what happened in those neighborhoods during this supposed war, it found that police had made no arrests and that the streets had been quiet.

Twitter, Donald Trump, and Fox News had all worked together to build a state of un-reality. They had, like the Pinkertons a century before, described a state of lawlessness and then sold the public on their preferred response.

But this isn’t some new manipulation which Trump has exploited for the first time. This is part of the social media business plan.

There has been a massive amount of research conducted over the past number of years on the role social media plays in radicalization and incitement to violence. These studies have told us an enormous amount about how the internet bends our brains and makes us prone to conflict. The world wide web hardens our own ideologies and grievances, we know, making us more likely to weaponize that anger into real-world violence against institutions or populations.

This trend is on full display in Trump’s emerging crusade to crush Antifa and the other domestic terrorists he has conjured up from the fog of paranoia and distrust present in his political movement.

But it isn’t the only story, here. The same trends which promote anger and hatred — created inside users’ filter bubbles, rewarded by platform algorithms and users’ social media habits — can also create fear. And there has been infinitely less study focused on how the internet makes us afraid.

In 2017, a trio of researchers set out to understand the emotional dimension around border security. Analyzing thousands of tweets, reacting to an announcement from then-President Barack Obama on immigration, they actually found that fear was the single-most common emotional response — and that it mapped closely onto anger.3

But the researchers found something even more interesting. In their modelling of the online discourse around border security, “fear, disgust, anger, and sadness distinguish influential users from less influential ones.” That is to say: If you want to succeed online, you need to know how to weaponize emotion.

We can see this trend from another direction.

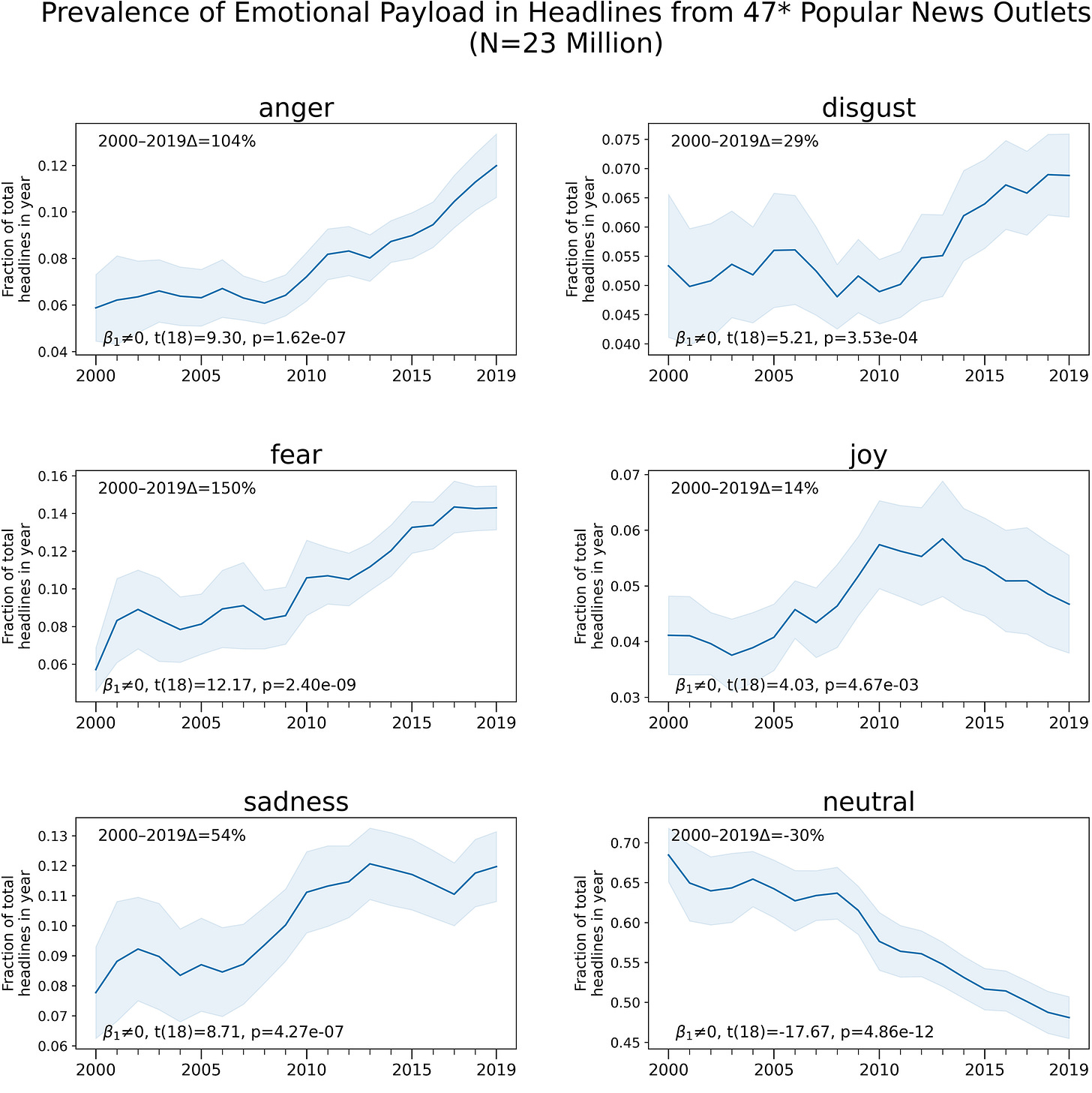

A couple of years ago, the New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology mapped out the emotional shift undertaken by major news outlets over the past two decades. Their study catches the exact moment when Facebook unveils its News Feed, in 2006, and the drastic effect it has on news discourse. You can see as these news publishers began refashioning themselves to meet the social media audience. The trend lines are terrifying, and there is good reason to think they’ve grown more intense in recent years.4

We can, and should, blame algorithms for some of this change. We, too, should blame the influencers, media personalities, and politicians who trade on these highly-potent emotions. But we also have to accept that the very nature of online engagement rewards content that makes you feel something.

As abstract a problem as this seems, it localizes itself in very intense ways.

In 2022, Emily Strickler, a master’s student at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, set out to study the role that neighborhood-based social media — chiefly, the local social media platform Nextdoor and neighborhood Facebook groups — played on social cohesion. She analyzed how communities in Las Vegas used these networks to stay in touch over the winter of 2020.5

These platforms, ostensibly, exist to facilitate engagement. They allow you to correspond with your neighbors at all hours, share updates, promote community events, and so on. But that’s not what they did.

“Use of neighborhood social media was found to have a negative association with how individuals perceived their neighborhood environment,” Strickler found. It seemed that the more you used social media to connect with your immediate neighbors, the people who you could walk down the street and say hi to, the less connected to them you felt. Social cohesion went down, sense of community declined, and fear of crime increased.

It’s important to remember that these groups are explicitly local — they are not infiltrated by Russian agents or bad-faith political actors. There, we are our own tormentors.

“Users frequently post and receive engagement on posts about issues such as mail theft, notices of strangers in the neighborhood, or what they perceive as suspicious activity,” Strickler writes. That kind of engagement is entirely organic — it can even be cathartic and necessary, a kind of steam release for frustration — but it also creates a distorted view by the neighbors who see those posts. “It is human nature to report and remember negative events over positive ones,” Strickler notes.

Imagine a porch pirate who targets a well-to-do neighborhood. They wait until the Amazon truck arrives and delivers parcels onto every doorstep on the cul-de-sac. The thief rushes up, loads every box into their car, and drives off. Over the next 48 hours, one-by-one, every house on the street posts their dismay: We’ve been robbed! The crime itself was exceptional and random. But a resident two blocks away, member of the local Facebook group, sees each one of these posts and thinks: This neighborhood isn’t as safe as we thought.

Producing content for social media costs virtually nothing, but it can be extremely costly to consume. When you post a status update, it can be a fleeting thought. When you read it, it can ruin your day.

That’s the exact phenomenon that two Australian sociologists sought to explore when they studied the impact of local social media in Queensland. They surveyed locals about their perception of crime, particularly as they experienced it through neighborhood groups on Facebook, WhatsApp, Nextdoor, and Neighbors — the social media platform run by doorbell surveillance company Ring. They went a step further, and sought out study participants who were also content creators, hyperlocal influencers.

Like Strickler, the study found that consuming content about crime on social media reduced people’s feelings of safety. Interestingly, however, they also found that “content creators expressed lower levels of perceived crime and higher feelings of safety compared to individuals who consume LBSM [locality‐based social media] only.”

We’re a few decades on from the advent of the ‘citizen journalist’ — that role has morphed and grown into the role of influencer. But we’re still grappling with the strange consequences of having a ton of regular people do a job, central to our democracy, that once required training, experience, and oversight. And we’re finding out that replacing journalists, whose job involves trying to situate news in context, with regular people, who are competing for attention online, is bad. People are freaking their neighbors the hell out.

It gets even more interesting. “We found that individuals who create content, react, share, and comment on LBSM feel safer than individuals who do not engage in LBSM,” they write.

So the more you feed the beast, the more you produce content for these social media pages, the better you feel about your community — but passive readers and viewers, there to get news and updates about their neighborhood, come off feeling considerably less safe and secure.

These localized social media communities are the easiest to study, precisely because they’re geographically-limited. But this phenomenon repeats itself nationally, even internationally. A spate of carjackings in Washington, D.C, shared widely on Twitter, can weaken someone’s sense of safety in Toronto, and vice versa.

Crime content simply does gangbusters. True crime remains arguably the most bankable genre of books and podcasts. Videos of conflict, theft, riots, and car chases are almost always guaranteed to go viral on TikTok and Twitter.

But crime in America has plunged since the early 1990s. The violent crime rate in 1993 was around 80 per 1,000 people: Staggeringly high. By 2015, that number had plunged to just 20. In the supposed post-pandemic crime surge, the rate hit 23.5.

Public perception of crime, however, is often decoupled from this data.

By the early 2000s, there was virtual unanimity: Americans reported that, with each year, there was less and less crime. But then, even as crime continued falling, perception of crime shot up. If the violent crime rate did increase, even just slightly, perception of it increased even more.

But there’s something interesting happening right now.

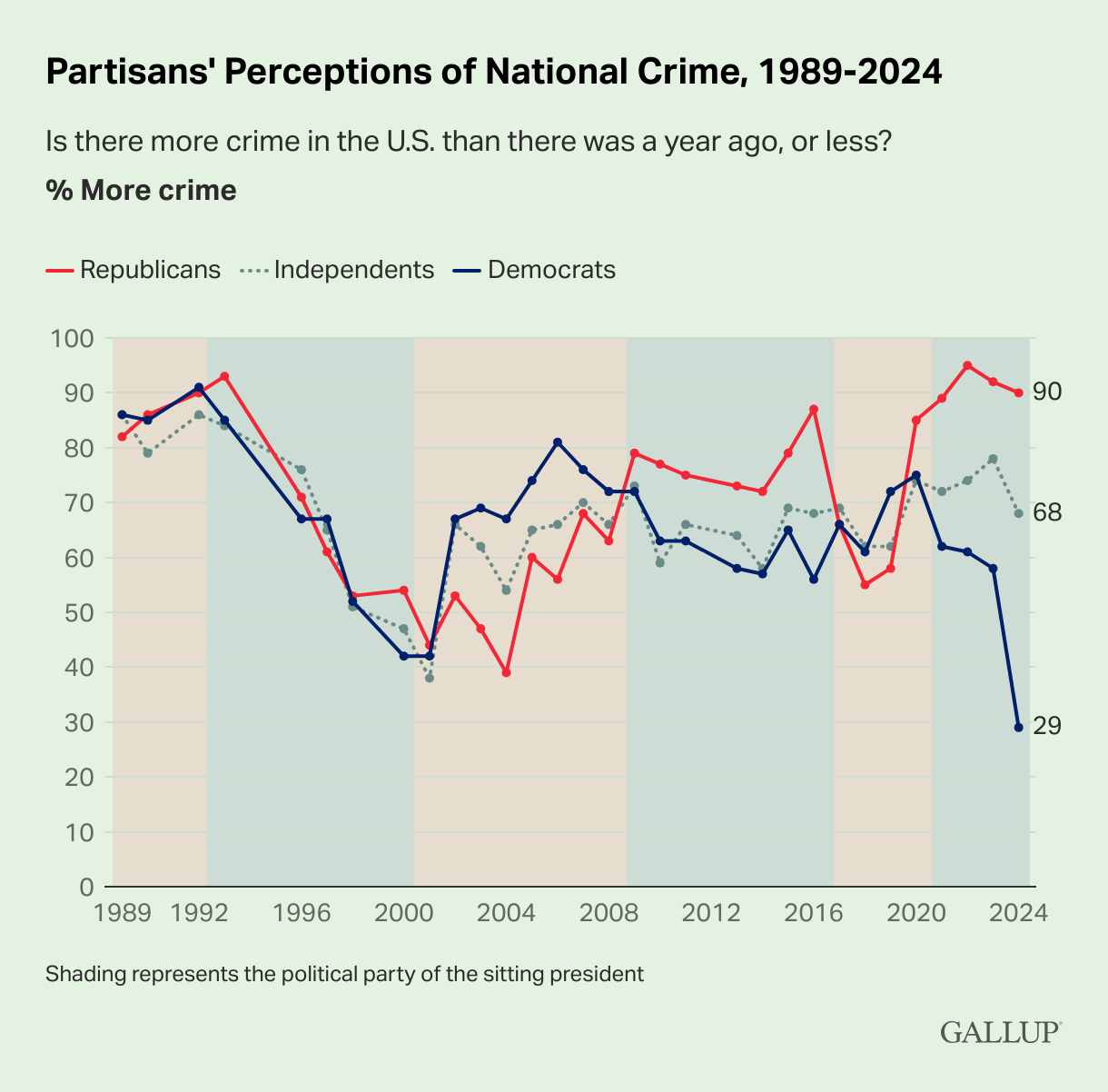

Over the past 12 months, perception of crime has dropped precipitously exactly as crime itself has fallen. This has been described as the public developing a more astute and accurate read of actual crime rates. Which is certainly true to a degree.

But, as survey data from Gallup shows, fear of crime has become radically divided along partisan lines. It is perhaps one of the most stark illustrations of affective polarization — of partisans fashioning their view of the world to comport with their political affiliation — that I’ve ever seen. There is simply no comparison to it.

Let me tie this all together: Fear of crime and disorder is an intense and tactile thing. It is perhaps one of the most reactive feelings in our society — something you can observe with your own eyes. Fear is also one of the most effective emotions to exploit for political ends, especially in invoking solutions that people would otherwise bristle at. These trends are as old as time, but social media is allowing bad actors to unfurl this strategy on a massive scale. Not only are fascists and propagandists deploying this against the public, but the public are opting in to this cycle of unreal fear. Social media firms, who once professed to care about healthy democracy, have abandoned all pretense and are reaping the profits of this mass delusion.

Crime is perhaps the sharpest example of how social media can alter our sense of place in our own communities. But there are so many different ways in which this happens.

There is a new kind of online space, one that I don’t think we’ve fully classified. But its prime example is 6ixBuzz.

6ixBuzz is, simply, an Instagram page for the city of Toronto. But, more broadly, it is a cross-platform hub for viral content, paid sponsorships, ragebait, parody, news, music, anti-vaccine bullshit, culture, and fear. It has a history of spreading misinformation, broadcasting political advertising, promoting racist content, and pumping-up clips of anti-social behavior.

6ixBuzz is a wildly warped mirror of the city of Toronto, and it is obscenely popular. It has 2.5 million followers on Instagram alone. And it has prompted a crazy number of imitators.

Some people have inferred political intent in 6ixBuzz, and I think they’re wrong. 6ixBuzz is a business. It stumbled onto all the same data I mentioned above, through trial-and-error. It had discovered how to make people angry and afraid, how it can alienate people from their own city — or, better yet, how to alienate rural and suburbanites from their nearest satellite city — and how it could prompt people to participate, contribute, and share their content widely.

There is now a version of 6ixBuzz in every major city in North America, to varying degrees. There are Facebook groups which started as community hubs that have fallen into rage, acrimony, and viral content of people behaving badly. Reddit is a repository of video of public freakouts, idiots fighting things, losers pretending to be badass, cops behaving badly, rogue Karens, and so on.

We are distilling the human experience to only the most extreme examples of human behavior. And it is significantly easier to film someone freaking out on an airplane than it is to capture someone getting news that they’re cancer-free, so we post and promote the former.

But not only are we consumers of this viral content, but we are expected to engage with it — and each other. Even though we know that the internet makes us less inclined to compromise, more inclined to distrust, and more susceptible to assuming bad faith, we keep engaging in these sprawling public online debates on the very same platforms that keep making us angry and afraid.

I know this sounds relatively elementary, as it’s essentially a description of the system that has become quintessential to modern society. But it is shocking the degree to which we are incapable of keeping these facts in the front of our minds. I have colleagues who have spent more than a decade as public figures on social media and who are still roiled by every mean post or wayward criticism. They spend orders of magnitude more time obsessing over a post than the person ever spent in drafting it. Worse yet, they mistake volume for intent — because they receive 200 negative tweets, they multiply the intensity of each tweet by 200.

We continue to find ourselves in the focal point of a magnifying glass being held up to the sun, and we are getting hotter and hotter. And we need to recognize that even if we can’t slap away the hand holding it, we can step aside.

That’s it for this week.

As some of you may have seen, I’ve started a new job! I am now a full-time columnist at the Toronto Star. You can read my first column as a full-on columnist here, and my mini-investigation into the Canadian connection to Donald Trump’s Bitcoin empire.

Here’s some great news, if you enjoy this newsletter: It’s not going anywhere.

At the Star, my focus is going to zoom in on Canada: Our national security, democracy, defense, sovereignty, and our relationship with Big Tech.

Here on Bug-eyed and Shameless, my focus will continue to be on all things information, particularly about how America is continuing to warp it for its own benefit.

And on Soft Power, I’ll have a new episode out very soon on the state of global humanitarian aid after the end of USAID.

So lots of stuff going on. I’m hoping to get back in the swing of regular newsletters in the near future. I’m at the Halifax International Security Forum this weekend, and I’m hoping to post some updates from it early next week.

[exhale] Until then!

Two Evil Isms, Pinkertonism and Anarchism: by a Cowboy Detective Who Knows, as He Spent Twenty-two Years in the Inner Circle of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, Charles Siringo (1915)

Inventing the Pinkertons; or, Spies, Sleuths, Mercenaries, and Thugs: Being a story of the nation’s most famous (and infamous) detective agency, S. Paul O’Hara (2016)

Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with Transformer language models, David Rozado, Ruth Hughes, Jamin Halberstadt (PLOS One, 2022)

Dissecting Emotion and User Influence in Social Media Communities: An Interaction Modeling Approach, Wingyan Chung, Daniel Zeng (Information & Management, 2017)

The Association between Neighborhood Social Media Use and Social Cohesion, Sense of Community and Perceived Safety among Adults in Clark County, Nevada, Emily Strickler, (UNLV Theses, 2022)

Congrats on the Star gig, Justin. Look forward to your columns there. But please, never stop with your great "deep dives" like this one here on Bug-eyed and Shameless!

Another great post, Justin. I always love your historical parallels, like the Pinkertons' in this case.

As you say at the very end, people do have the option of not participating. The best news I've seen recently is that social media use may have peaked. (Source: Financial Times, as reported by Bill McKibben; ref. https://erwindreessen.substack.com/i/175123026/social-media-use-may-have-peaked)

I fear that the return to sanity will be a long road, however. A November 2023 study published in the International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction concluded that a third of adults around the world qualified as addicted.