"Read the Donroe Doctrine To Them"

The thing about hegemony is that it, unfortunately, works. And it crushes real democracy along the way.

William Walker was greeted in Nicaragua as a liberator, by some.

Walker was a lawyer and newspaper publisher who had become obsessed with the idea of expanding the United States southward. He got into the business of leading bands of armed men to declare the creation of new, civilized, states. They were freebooters, or filibusterers.

Nicaragua had been independent for some decades, and it had been racked by civil war and infighting. Part of the country had grown rich, thanks especially to investments from American oligarch Cornelius Vanderbilt who built a complex network of steam lines, stage coaches, and railways which could carry gold prospectors from New York, through Nicaragua, to San Francisco. This nouveau riche was concentrated in the city of Granada, who supported the Conservative Party.

But much of the country remained rural and poor. And they turned to the Liberal Party. Forced from power by their Conservative rivals, the Liberals turned to William Walker.

Walker and a boatload of American mercenaries landed in Realejo in 1855. This filibuster was there for one purpose — to colonize.

This was the strange era of the Monroe Doctrine, a nebulous concept of Washington’s dominance in the Americas. Its namesake, President James Monroe, didn’t contribute much to the concept beyond a single speech. (“The American continents…are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.”) It had, rather, become a slogan that could be used to justify all manner of U.S. action in Latin America, good and bad.

“If we want Central America, the cheapest, easiest, and quickest way to get it is to go and take it,” proclaimed Senator Albert G. Brown in 1858. “And if France and England interfere, read the Monroe Doctrine to them.”

In this strange era, Americans believed they had both the right and the duty to stretch their arms throughout the continent — and with it, they could civilize the savages through the establishment of massive plantations reliant on slave labor.

They organized, amongst other ways, in the Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret society of American secessionists who wanted a massive slave-holding empire wrapping around the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Others, of course, focused on seceding from the United States first.

Walker didn’t wait. Invited as a liberator, he made himself king in 1856. One of his first acts, even as he continued fighting local forces, was to legalize slavery — giving Nicaragua the odious distinction of being the only country in the Spanish Americas to abolish the enslavement of man, only to re-institute it.1

“That which you ignorantly call ‘Filibusterism’ is not the offspring of hasty passion or ill-regulated desire,” Walker wrote in his memoirs, “it is the fruit of the sure, unerring instincts which act in accordance with laws as old as the creation.”2

That ‘law,’ he invokes is grotesque race pseudoscience: The idea that a pure white race can and must subjugate supposedly savage peoples. “Whenever barbarism and civilization…meet face to face, the result must be war.”

Walker’s occupation of Nicaragua would only last about two years. While he never did actually restart the African slave economy, he did force poor Nicaraguans onto the plantations and unleash a huge amount of violence and sickness on the country. So offensive did Walker become that he was opposed not only by domestic Nicaraguan forces, but also by soldiers from Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and resources sent by Vanderbilt — whose business interests Walker had nationalized.

Walker’s regime eventually fell, and he attempted to burn the whole country down as he staged a hasty retreat. In a bizarre twist, Walker was eventually forced into capitulation and captured — not by local forces, but by an American commander.

Walker blamed his downfall on “the cowardice of some, the incapacity of others, and the treachery of many.” But, he swore, he had “yet written a page of American history which it is impossible to forget or erase. From the future, if not from the present, we may expect just judgement.”

He was, unfortunately, right. While the United States government had been hostile to southern slavers’ adventurism in Latin America, and annoyed at the diplomatic headaches caused by the freebooters, it eventually made expansionism state policy. In the years that followed, it occupied Guam, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and a host of other states — sometimes annexing the territory for good. America invaded, meddled, and overthrew governments in the name of building canals and promoting the banana trade; it blockaded ports and collected debts; it used tariffs and economic power to bully Latin American governments into subservience. In 1912, America invaded Nicaragua and occupied it for nearly 20 years.

Walker didn’t live to see any of this. Upon trying to return to Central America in 1860, he was arrested by the British and handed over to Honduras. At 36 years old, Walker was tried, convicted of filibusterism, and executed.

Walker wasn’t an aberration, however. His mistake was launching his adventurism too early. It was America’s position that its race, riches, and might gave it a special authority to decide the fate of its southern neighbors — perhaps its northern neighbors, too. President Teddy Roosevelt codified this in his Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which restyled America, a “civilized society,” into an “international police power” which was free to punish “chronic wrongdoing” or even just “a general loosening of the ties of civilized society.” Washington had the free hand to define those terms as it saw fit.

America would, over the years, grow mortified at this era and try to forget all about it. Roosevelt’s cousin, Franklin Delano, would replace his Corollary with the “Good Neighbor Policy.” Nearly a century later, after the policies came back in vogue in the name of fighting Communism, Secretary of State John Kerry would try to bury it even further by proclaiming the Monroe Doctrine “dead.”

Well, it’s back.

In December, President Donald Trump unveiled his National Security Strategy — the Donroe Doctrine, the “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.”

With it comes Trump’s racketeers, his gangsters for capitalism.

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to talk about an American ideology of meddling, theft, piracy, regime change and occupation.

And how it will work. At least, for a time.

There is a phrase in America’s recently released National Security Strategy that is so absurd, so simultaneously meaningless and terrifying, that I can’t help but marvel at it.

The United States now operates on the basis of “Flexible Realism.”

I remarked a few months ago that you can’t be a realist if you’re an idiot. (Dispatch #138) The administration has unknowingly offered a rejoinder: Fine, they say, we won’t be real realists.

The strategy promises America will “seek good relations and peaceful commercial relations with the nations of the world without imposing on them democratic or other social change that differs widely from their traditions and histories.” At the same time, it will “push like-minded friends to uphold our shared norms, furthering our interests as we do so.”

You don’t have to stretch your imagination to realize that this will mean even better relations with despotic, corrupt, criminal regimes and worse ties with liberal, transparent, democratic governments. (Indeed it also promises to boost “patriotic” European political parties.)

Some of the (ir)rationale of this new policy is economic. Trump has made it abundantly clear that he is hungry for the billions of petro-bucks offered up by the Gulf states, while he sees Europe and Canada as competition for manufacturing jobs.

Some of it is a matter of inter-personal relations. Autocrats are simply more free to flatter and sooth, whilst European leaders can’t be seen looking weak to their populations of horrified voters.

It is also a function of racism. Trump sees white Europeans as failing to uphold their birthright as Europeans, whereas nationals of every other country are judged based on his preconceptions of their heritage. (Wise sultans of the desert, Somalians come from a “shithole,” the Middle East is full of radicals, sneaky Chinese, etc.)

More broadly, it really is a question of values. Trump does not value cooperation or the shared norms he claims to represent — and he doesn’t want other countries putting too much value in those things, either. More than anything, he does not value democratic legitimacy. If anything, it can be a sign of weakness.

This is all stuck in here in this foreign policy document, couched under the language of “realism,” because it is a signal that America intends to return to an era where any and all action can and will be rationalized by a guiding philosophy so amorphous and incoherent that it could be simultaneously interpreted to suit non-intervention and intervention; trade or blockade; yes and no.

And, lo, that’s exactly how it’s being deployed already.

In Venezuela, flexible realism has justified a Potemkin coup d’état — the symbolic removal of a criminal president to transform the state into an oil-supplying client. In Iran, Trump seems to be weighing between installing a chosen king with keeping the murderous state as is. Finally, in Greenland, Trump has put new vigor behind his plans to build a hemispheric empire.

However morally bankrupt and absolutely brazen this is, it is incredibly likely that America will eke out marginal wins on each of these files. And, in each of those tales, a genuine democratic and popular movement is being crushed along the way.

Gangsters for Petroleum

Late last year, I got to meet David Smolansky.

His family hails from Ukraine, where his grandparents fled the totalitarianism and antisemitism of the Soviet Union; relocated to Cuba, only for his parents to quit under growing pressures from the the Communist state; landing finally in Venezuela. In 2013, Smolansky ran for mayor El Hatillo, one of the municipalities within Caracas, with the centre-left opposition Popular Will party.

The Venezuelan state had been wobbling when President Hugo Chavez ran for re-election in 2012. He won that election, marked as it was by intimidation and violence, albeit more narrowly than anyone expected. When Chavez died the year after, the hastily-installed Nicolas Maduro moved quickly to call fresh elections.

Wobbly as it was, the Venezuelan state was still faring relatively well. Inflation was growing, but manageable. Oil royalties were dropping, but oil demand looked strong going forward. Arguably the largest issue for voters was rising crime.

Maduro claimed victory in those elections, but just barely (and through some fraud, the opposition said). But so, too, did Smolansky. Things didn’t get better — they got much, much worse. Oil production and revenue bottomed-out, crime rose, inflation skyrocketed. And the regime spent its time arresting and hunting down opposition leaders.

“If this isn’t a totalitarian system, then I don’t know what can explain what is happening in this country,” Smolansky told the Associated Press in 2014.

As of late last year, UNHCR estimated there were nearly 8 million Venezuelan refugees and emigres who had fled the increasingly-despotic, violent, corrupt, and incompetent regime. Smolansky is one of them: In 2017 he was removed from office and sentenced to prison for failing to crack down on anti-regime protests. Knowing what awaited him at home, Smolansky fled — and became an advocate for his compatriots who lived in exile against their wishes.

“The only solution is regime change,” he said in 2021. It was a recognition of a political leadership that had so corrupted itself and the state around it that there was no reform that could ever salvage it. The Maduro regime had deployed extensive lethal force against its own people, and had committed to disabling the already-weakened democracy which had run for decades.

Compounding the social crisis was an economic one. Over about 15 years, Venezuela earned about $800 billion in oil revenues — but the state had hardly delivered that amount worth of social services. Investigations began to uncover why: Tens of billions of dollars were discovered in bank accounts tied to employees of state companies and their political minders. As time wore on, the corruption ran the oil rigs into disrepair and output plummeted.

Plenty was stolen under Chavez, when times were good. When the theft continued into bad times, things got worse. To make up the difference, Maduro sent oil to China and Iran; it snuck gold through neighboring countries; and it liaised with rebels and gangs to trafficking huge amounts of Colombian cocaine.

The Venezuelan people tried to finally exorcise this ghoul through the 2018 elections, which were widely condemned as fraudulent — including by the Venezuelan people. There were protests, sanctions, crackdowns. They tried again in 2024: Same fraud, same protests, same crackdown.

Smolansky had been right all those years ago: Regime change was necessary. Indeed, the Venezuelan people had tried very hard to change the regime, and the regime couldn’t take the hint.

When I met Smolansky, at the Halifax International Security Forum last November, he was grinning. He was working closely with Edmundo González, the opposition figure who almost-certainly won the 2024 election; and María Corina Machado, the protest leader who had just won the Nobel Peace Prize. He was sure that it was going to happen. The regime was finally going to go.

Why? Because Donald Trump.

He didn’t seem to think it would be through military action, though maybe. He believed that concerted pressure — stronger sanctions, more action on Maduro’s drug-trafficking empire, pressure on Venezuela’s few remaining allies — would finally give the regime the one last push it needed to fall. Although, would targeted military action really be so bad, if it meant the regime would stop killing its citizens?

Fast forward a few months, and it happens. Missiles pound Venezuelan military installations and American MH-47 Chinooks fly low over the capital with marines aboard, tasked with grabbing the kleptocrat.

As the raid unfolded via cellphone footage and rampant online speculation, one interesting question percolated: Where the hell are Venezuela’s anti-air systems?

Caracas had spent years buying advanced Russian air defense systems — Secretary of War Pete Hegseth even joked about it after the fact. (“Seems those Russian air defenses didn’t quite work so well, did they?”) And yet not a single American plane had been hit, apart from one Chinook hit by small arm fire.

If America had knocked offline the entire Venezuelan defense apparatus, it hadn’t killed many people while doing so. An estimated 57 Venezuelans died in the raid, including two civilians, 32 Cuban security personnel, and 23 members of the Venezuelan military — including, reportedly, Maduro’s personal bodyguard Juan Escalona.

Perhaps the Venezuelan defensive systems were poor, badly kept, not manned, jammed by American cyber and electronic warfare systems, bombed into inconsequence, or otherwise not online.

Or, perhaps, the Venezuelan military were told to stand down.

It felt awfully speculative, at first. Why would the regime permit such an operation?

And then, hours after Maduro had been snatched and hauled to New York, Trump made a perplexing statement. Asked directly as to whether he would support Machado as the interim president, Trump demurred. It would be, he said, “very tough for her to be the leader,” given she “doesn’t have the support or the respect within the country.”

America had removed Maduro but it hadn’t overthrown the regime. In fact, his operation had kept it perfectly intact. So much so that Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodríguez, simply took over.

Heightening the surrealism of this transfer of power: Earlier this week, Rodríguez appointed Juan Escalona, Maduro’s ex-bodyguard, as the minister responsible for her presidential office — the same bodyguard who had, reportedly, been killed in the raid.

This has all suited Trump fine. “We’re in charge” he proclaimed, warning Rodríguez that “probably worse” fortune will befall her if she resists American demands.

And demands, America has. “We’re going to take our oil back. Well we’re going to run everything. We’re going to run it, fix it.”

Rodríguez seems fine with this arrangement. She has been an integral part of Maduro’s narco-state. In 2017, as the country’s foreign minister, she set up a $500,000 donation to his first inauguration committee, directly from the cash-strapped state oil company. There’s good reason to think her penchant for flattery has continued.

Already, America has gone on a spree of seizing Venezuelan oil tankers, and the hobbled Venezuelan state doesn’t seem to be trying very hard to stop it. While there has been ample skepticism that American energy firms will be willing or able to reboot the moribund Venezuelan petroleum industry, it almost doesn’t matter: Donald Trump has taken out a chief villain of the American imagination, he has stolen a bunch of oil, and he has groomed a pliant and autocratic regime to do his bidding under the threat of violence.

This new regime has done the bare minimum to appear different. By Tuesday, Caracas authorized the release of 56 political prisoners: Just 5% of the estimated thousands who sit in Venezuelan prisons.

For Trump, this is inconsequential. “We’ll have elections at the right time,” he says.

And so, what? America has proved, once again, that it decides who governs. It decides what regimes survive and which fall. It decides who is legitimate and who is not.

Last week, Smolansky spoke to Christiane Amanpour: “I don’t have any doubt,” he said, “and I want to reiterate that Maria Corina Machado and Edmundo Gonzalez are going to lead the rebuilding of Venezuela.” It is Machado and Gonzalez who can “guarantee us a great alliance with the U.S., a great alliance with the democratic countries in Latin America, a great alliance with the European Union.”

His optimism is admirable and I fully believe that one day soon he will see an independent and democratic Venezuela. But much as his family has fled from one increasingly-depraved dictator to another, I’m afraid he has found himself at the mercy of yet another autocrat with little concern for democracy.

On Tuesday, the Economist released the results of a new poll of the Venezuelan people. More than 50% support the capture of Nicolas Maduro, fewer than 15% oppose it. Nearly 80% report feeling optimistic about the future of their family and country. And who do they want running the country? Of all the available options, nearly 50% said Machado, while nearly 10% said her compatriot González. Barely one-in-ten said Delcy Rodríguez.

And yet so long as Delcy Rodríguez best serves Trump’s interest, that’s what the people of Venezeula will get.

There can be no better illustration of this bait-and-switch than the dual meetings which happened Thursday. Machado visited the White House to hand Trump her Peace Prize, an act of cringe-worthy submission that would be worth it if it won the state freedom. At the same time, CIA Director John Ratcliffe was in Caracas to meet Rodríguez to finalize their “improved working relationship.”

Trump is creating a banana republic, in the truest sense of the word.

In 1931, General Jorge Ubico assumed total control of Guatemala, abolished democracy, and set about making the country the best friend America could have — by handing over obscene amounts of control to the United Fruit Company. He considered himself a virtual reincarnation of Napoleon. He banned the words “trade union,” “strike,” “petition,” and “worker.” The peasants who tended to the crops were required to work a minimum of one hundred days per year and anyone who failed to respect the orders of their employer could be legally killed. 3

He would remain in power for 13 years, thanks to support from American government and business, who were simply swimming in cheap bananas.

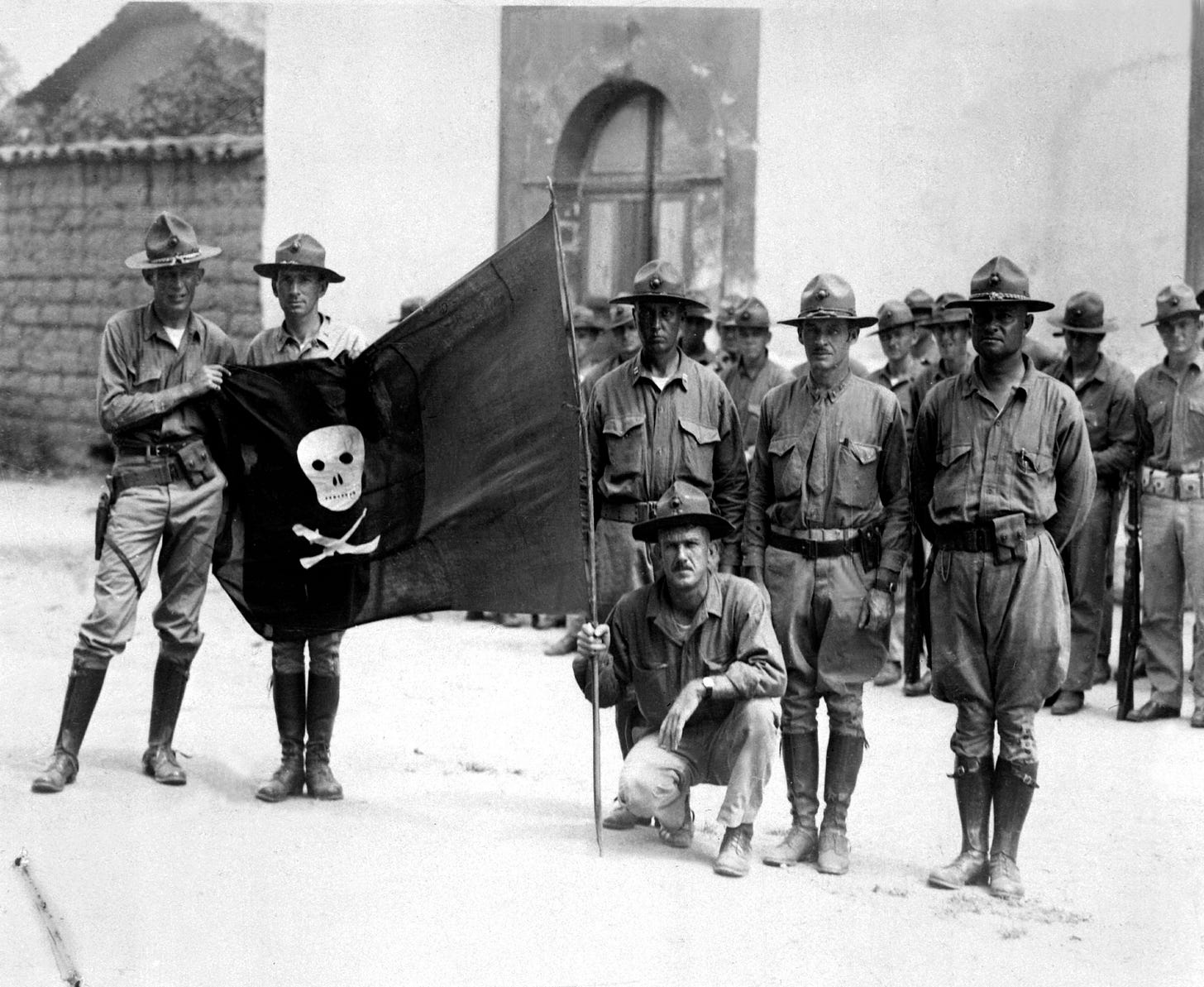

Major General Smedley Butler, who led marines to invade and occupy throughout the Americas, looked back on his time in the region with horror. “During that period, I spent most of my time being a high class muscle-man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the Bankers,” he wrote years later.

“In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism.”

“We do control the destinies of Central America and we do so for the reason that the national interest absolutely dictates such a course … Central America has always understood that governments which we recognize and support stay in power while those we do not recognize and support fail.”

-Secretary of State Robert Olds (1926)

To Shah Or Not To Shah

In 2009, I had just graduated highschool and found myself reading inscrutable instruction manuals on how to create a VPN tunnel.

Through trial and error, and much swearing, I eventually saw a tiny green dot light up on my laptop’s command bar. Someone, somewhere on the streets of Tehran, was accessing the open internet through my connection.

Twitter had only existed for about three years — and was still about two years away from helping to spur and maintain the Arab Spring — but it had become the go-to resource for thousands of young Iranians as they took to the streets to protest a stolen election. It was the place where you could announce where the nightly protest was set to occur; report the movements of the Basij, the feared Iranian militia tasked with keeping order; and post photos which could go globally viral.

For generations, frustration with the theocratic regime of the Ayatollah and his mullahs had ebbed and flowed, but the state had always been adept at using repression and reform in equal measure to quell dissent.

Even if Iran’s democracy had existed within tight rules, Iranians had, up until then, the ability to elect their president. But in 2009, the mullahs had meddled to protect nutjob incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad at the expense of reformist Mir-Hossein Mousavi. The people revolted by the millions.

The crackdown killed dozens and showcased the extent to which Tehran could and would lock down society to prevent unrest. The endemic internet censorship which necessitated the very kind of VPN tunnel I ran on my laptop scaled up to build the so-called ‘Halal Internet.’ The Basij grew more powerful, Iran grew into a regional power in defense of theocratic autocracies everywhere, and the people of Iran were told they could never be free.

So the Western world sighed and tried, at various times, stiff sanctions and indirect support for Iranian civil society, followed by earnest negotiations and attempts to deal with the regime. While the topic of war and regime change came up occasionally, it was generally dismissed as warmongering.

And then, last June, America and Israel unleashed respective missile barrages targeting Iranian nuclear sites. The quasi-war was frenetic, pointless, and ultimately a resounding success for America.

Trump got to claim he destroyed Iran’s ability to end the world and suffered nary a bloody nose for the trouble.

This did nothing, of course, to destabilize the regime. If anything, it solidified it. The Ayatollah and his lackeys, giddy with defeat, told their population that a hungry American wolf lurked in the shadows, ready to devour them all. Fear kept the regime alive.

Today, Tehran faces too many mounting crises. It has faced persistent price inflation for a decade, with food inflation recently hitting 68%, as its currency has become internationally worthless. Sanctions have hampered its ability to do just about everything, and its constant war footing has depleted its reserves. To top it all off, it didn’t rain.

Endemic mismanagement of Tehran’s abundant aquifers and droughts worsened by climate change meant that the country’s capital had literally run out of water. “Water bankruptcy.” The murderous gerontocracy announced it had no choice but to move the capital.

Regular people have a much better solution: Oust the broken regime. Protests have roiled the entire country. Now capable of circumventing Iran’s impotent firewall in interesting new ways, Iranians have managed ubiquitous and locally-organized unrest.

The state is functionally paralyzed and the regime’s last remaining tool was to unleash mass murder. Reports from inside Iran put the death toll at 2,403. Tens of thousands of others are believed to be in prison. (The final death toll could be much higher.)

This is probably the most serious threat to the regime in its entire 47-year existence. Its population has never been angrier and more desperate for change, and the state has never been less capable of feigning normalcy. The compendium of possible outcomes is massive and could get extremely bad.

In that context, the possibility of American intervention isn’t inherently bad. Much as if America had seized Maduro and immediately recognized Gonzalez, Venezuela may have been able to make a relatively-seamless transition from kleptocracy to democracy; there’s certainly a world in which American military might could cause enough damage or stress to the Iranian regime that a popular opposition could overrun it.

But this is a world where Donald Trump is president.

As images of the Iranian protests have hit the news, Trump has vowed to the Iranian people that help is on the way. Reports have emerged that the administration is considering strikes to decapitate the regime.

Much as with forecasting anything in the Trump regime, you always need to look to three places: What do JD Vance and Stephen Miller think; what do the Gulf States want?; and who’s buying facetime in Mar-a-Lago?

On the latter question: The supposed “Crown Prince” of Iran, Reza Pahlavi. He’s been eager to encourage the street protests, and Fox News was immediately happy to have him on while preeminent Trump-whisperer Laura Loomer aggressively took on his cause.

Pahlavi has been billed as, despite his hereditary title, a transitional leader who could carry Iran into democracy. And based on the chants from the streets he’s become a popular figure in Iran itself. Or, at least, the idea of him has.

But Trump’s primary benefactors in the region — Qatar and Saudi Arabia — have vastly contrary views on the regime. Doha has always been close to Tehran, whilst Riyadh has always been a rival. Neither seem to want to see the state collapse, but neither are likely to want a genuine democracy either. More likely, both states would like to see a fellow monarchy flourish in Persia.

Pahlavi is, however, a weak figure with zero democratic legitimacy. If America were to install him as leader, he would be caught between the incredibly-difficult work of bringing-together the disparate factions across Iran, building its institutions from the ground-up, and preparing for democratic transition. It’s hard to believe that Trump or the sultans of the Gulf care about any of that.

Even still, that might be the best-case scenario. Per the Wall Street Journal, the Vance-Miller shadow presidency seem keen to repeat their apparent success in Venezuela: Keep the state, but make it subservient.

The paper reported this week, backed up by Vance’s own comments, that Vance is pushing for Trump to skip strikes on Iran in favor of “real negotiation” over “what we need to see when it comes to their nuclear program.”

Vance has tried this before. Last year, he made a big to-do, touting progress in nuclear talks with Iran. Trump bombed them anyway, so Vance declared it mission accomplished.

It seems unlikely that Vance and his ilk genuinely want progress on a nuclear deal. For years, he has touted himself as the only person in the world who truly cares about nuclear disarmament. Every other effort to reduce the number of nuclear weapons in the world, he has argued, is weak and bad — notably, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action which was actively setting up for a reduction in Iran’s stockpile. The first Trump administration exited that deal, leading to a significant increase in Iran’s enrichment program.

Vance has held up that chain of events — which his own president caused — as proof that nobody cares about nuclear non-proliferation. How would Vance do things differently? He’s never said.

Scratch a bit, though, and you’ll find that this really isn’t about nuclear weapons or regime crackdowns at all.

On the contrary, the ethno-nationalist camp within the White House is not taking a non-interventionist position in the Middle East on principle, but rather because it sees Iran through a one-dimensional lens of “Islamism.”

For years, Stephen Miller has described Trump’s crusade against Iran as a means to “curb destabilizing Islamist violence and prevent Iranian hegemony.” He has alleged that the Democratic Party is financed by “a vast shadowy dark money network” with “foreign ties” — including Iran. He has written that Trump’s travel ban on Iran kept out “pro-Hamas foreign students” from America’s universities.

Vance, for his part, recounted a bizarre anecdote to a conference last year. He recalled asking a friend: “What is the first truly Islamist country that will get a nuclear weapon?” He answered his own question: “Maybe it’s Iran. Maybe Pakistan already kind of counts. Then we sort of finally decided; maybe it’s actually the UK, since Labour just took over.” Ha ha ha.

Let me frame this in simple terms: JD Vance and Stephen Miller believe that Iran is a backwards country of extremists who, through their very existence, represent an existential threat to America and must therefore be contained. In their minds, a popular uprising is meaningless, as it would just swap one kind of “Islamism” for another. It would be better to keep the devil you know in power, as he would be weakened and reliant on American goodwill for his continued existence. That comes with the added benefit of pointing to a far-off evil power who can be blamed for all unrest at home.

In the same way that Venezuela’s legitimate political actors have been used and cast aside in favor of the Maduro regime with a new hat, the people of Iran are considered as an afterthought and a liability — at best, a tool to achieve American objectives; at worst, a hindrance to America getting what it wants.

Certainly, America has pursued rabid self-interest before. And it has allowed ideological frames to justify its overseas activities. But never before has America so resembled the filibustering of William Walker and his freebooters. This isn’t a foreign policy, it’s piracy.

One Way Or Another

There is a common story which marries the current predicament of Venezuela and Iran — their corrupt states trace their legitimacy to illegitimate American action. A series of successful and botched invasions and coups through Latin America had bred endemic distrust of America in the region, a fact which Hugo Chavez exploited to great effect. The 1979 uprising which crowned Ruhollah Khomeini as Ayatollah, meanwhile, was spurred by hatred of the American-installed Shah (father of Pahlavi) and his brutal secret police.

By contrast, there is no particular animus between Greenland and America. In fact, it is quite the opposite.

In 1940, the prospect of Nazi Germany invading and occupying Greenland was very real. Germany invaded and occupied Denmark early that year — meaning the Third Reich, technically, could claim Greenland. The Allies couldn’t accept an enemy staging ground in the middle of the Atlantic, and America couldn’t tolerate such an impingement of the Monroe Doctrine. (Indeed, one of the most clear-cut examples of what the Doctrine actually invoked.)

But it wasn’t quite clear what America, still not a party to the war, would do. Two Danes — Eske Brun, a Danish administrator of Greenland; and Henrik Kauffmann, the Danish ambassador — convinced Washington to extend its protection to the Arctic.

The Agreement Relating to the Defense of Greenland acknowledged “the grave danger that European territorial possessions in America may be converted into strategic centers of aggression” which obligated America to occupy Greenland. But, it noted, “the sovereignty of Denmark over Greenland is fully recognized.”

America could have installed its own general to run Greenland, and it could have fully annexed the island. It didn’t: Brun assumed control as governor while Kauffmann became its main interlocutor in Washington.

And it was Brun, who actually understood the island, who came up with the idea of the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol.

The Patrol consisted of Inuit Greenlanders as well as Norwegian and Danish hunters who were tasked with patrolling the vast expanses of the remote northern half of the island — if they detected evidence of human activity, U.S. Coast Guard cutters were called to respond.

In early 1943, a Danish-Greenlander sledge team, and their curious dogs, discovered something unusual in the snow, in a remote corner of the island. “Footprints, human footprints — boots, with heels!”

The prints led them to a German outpost on the island. The Nazis, who had little visibility in the mid-Atlantic, desperately needed a weather station to aid their U-Boats: And they had set up a secret one, right there on Greenland.

Armed only with rifles, and with backup far off, the sledge team engaged the Germans and won: Taking a German commander prisoner. It was the first of two major engagements with the Germans on the island: One Dane would give their life defending Greenland.

It is no exaggeration to say that these men were the difference between the Germans gaining the freedom of navigation in the mid-Atlantic and their continued vulnerability to the weather. That mattered a great deal.

Those years, and the decades since, have underscored the enormous utility in cooperation. In 1951, after Greenland returned to Danish control, Copenhagen and Washington signed a new defensive pact. It maintained that territory on Greenland could be used by the United States, with some mutually-agreed caveats: The territory would remain Danish, but America was free to use its bases for whatever purposes it needed — so long as that included the defense of the island. It was nearly incomprehensible that American and Danish interests could even diverge. Through the Cold War, some 10,000 American personnel were stationed on the network of bases and radar stations on Greenland.

In 2000, recognizing that American presence had come at the cost of forcibly-displaced Indigenous populations, America returned a swath of land back to Greenland and significantly reduced their presence on Greenland. Today, just 150 U.S. Air Force and Space Force personnel are still on the base.

Over that time, Greenland began exercising its own political autonomy. It demanded, and won, home rule; it quit the EU in protest of lax fishing regulations; and won full self-governance in 2008. (All three were supported by popular referenda.) Through the 21st century, it modernized its economy with a pretty transparent goal of weening off the block grant sent by Copenhagen.

Last year, Greenlanders were asked: Do you want to be independent?

A paltry 9% said “I don’t want independence.” The rest endorsed independence, to varying degrees of urgency. Asked if they would like to leave Denmark and become a territory of the United States instead, the responses were even more resounding: 6% for, 85% against.

That, apparently, doesn’t matter. “One way or another,” Trump has proclaimed. “we’re going to have Greenland.

“If we don’t do it, Russia or China will, and that’s not going to happen when I’m president.”

I’ve written before about Trump’s delusional views on Greenland, and how it may yet result in NATO taking the Arctic seriously. (Dispatch #123) The fact is, Russia has invested heavily in its Arctic capabilities, and now far outmatches NATO in terms of its ability to project power in the northern waters. China, meanwhile, is fast at work building icebreakers and has made an open entreaty to Arctic powers for economic investment.

There is little appetite for more Russian presence in the north, but China’s engagement has been met with some more warmth. Capital inflows could help Nuuk finance the kind of mining, energy, tourism, and other projects that would be necessary to hold such a referendum and survive the loss of their Danish block grant.

Chinese economic control of Greenland would be a threat to North America.

The trouble is, that hasn’t really happened. Plans to acquire a major Greenlandic port and airport from Chinese companies were blocked by the Danes. Mineral exploration projects from Chinese firms were either abandoned or put on hold due to environmental concerns. Beijing, it seems, has gotten bored and moved on.

If America seriously cared about countering and deterring Russian movements in the north, it would station more personnel on its expansive military base already in Greenland. If it cared about preventing Chinese capital from flowing into the island, it would step up with its own direct investment which is sorely wanted.

But it hasn’t really done either. Because Donald Trump doesn’t really care about protecting the hemisphere from hostile foreign powers. He wants to be the hostile foreign power.

It will, like I’ve written, probably work in Venezuela and Iran. Who, after all, is going to stop him? Who can make Trump side with democrats over despots, who can make him respect international law? Nobody, it seems.

The American hegemon is powerful enough to force marginal wins — but it inevitably, invariably fucks up. You can’t keep toppling, invading, occupying without eventually making yourself weak. Maybe you spend too much money on global adventurism, maybe you alienate your own people, maybe you breed a population of foreign-born people who hate your habit of meddling, maybe you stymie the very kind of cooperation that helped make you strong. But, eventually, you bungle it.

I think if Trump forces the Greenland issue, it will be the line in the sand. It will be the break that will finally roil his out-of-control administration. It should be the clarion call for Canada and Europe to finally stop placating and start protesting.

Trump’s sophomoric obsession with capturing territory is both pathetic and deadly serious. It is offensive on its face and a signal for dangerous times to come. But, in levying these threats, Trump made a facile aside that leapt out to me.

“Basically, their defense is two dog sleds,” Trump told journalists. “You know that? You know what their defense is? Two dog sleds.”

Yeah, dog sleds that helped America win World War II.

Happy new year, readers. I’m trying to start January with a bang: I’ve been writing, rewriting, rewriting thoughts on three of these files — Venezuela, Iran, Greenland — for the past two weeks, and I finally pulled the trigger and smushed them all together.

There’s fresh Soft Power on the way, and another big Bug-eyed and Shameless dispatch in the pipeline. Over at the Star, I’ve just penned a long piece on how Canada can stand up for Greenland.

Until next time!

Confronting the American Dream: Nicaragua Under U.S. Imperial Rule, Michel Gobat (2005)

The War in Nicaragua, William Walker. (1860)

The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King, Rich Cohen. (2013)

Do you see a similarity between Hitler stretching himself thin on multiple fronts and Trump’s domestic and foreign forays?