Peacemongers and Peacemakers

After three years of war, Ukraine risks being sold out

In the lobby of the Pasazhyrskyi railway station in Kyiv there is a giant crystalline heart, suspended just above the ground.

Intermittently, the heart flashes red. Funeral black text appears on the screen encasing the massive glass organ. 1

Palichuk Serhiy, a person with a big heart! A loving husband, father, and grandfather. Forever 52 💔, Zhrub-Komaryvskyi village, Storozhynets Raion.

Varvara, my close friend. Died at 14. Mariupol.

The guys from Trudova Street – Denys Kozhevnikov and Mykhailo Savchuk. Thank you for your protection, guys. Eternal memory. Kostiantynivka.

My dear little brother Makarets Viacheslav. I am proud of you and miss you terribly, 48. Donetsk.

Holynska Sofiyka. Forever 6 💔 Kyiv.

Ukrainians have submitted more than 2,000 names into this Heart of Ukraine installation. Those names are just a fraction of the tens of thousands killed by this war — from Russia’s initial invasion in 2014, to its unleashed aggression in 2022 and the brutal three years that have followed.

As a physical manifestation of the scale of the loss, Heart of Ukraine is sobering. But it is, I think, in the wrong location. Those who come and go from the Pasazhyrskyi railway station — as Justin Trudeau and Ursula von der Leyen did this week — know full well the damage done to Ukraine and its people.

The Heart of Ukraine should be installed on the White House lawn. Its occupant has just succeeded in strong-arming Kyiv into signing a resources deal at the barrel of a gun, and now he is set to capitulate on Ukraine’s behalf, slobbering on the feet of a dictator in the name of making a deal.

But this week, on a very sober Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to outline the pitfalls waiting for Donald Trump as he attempts to wrestle the bear. How he proceeds in the coming weeks will have enormous ramifications for not just Ukraine, but the whole world.

Yet we would be mistaken for thinking that it is all bad news. Ukraine and its allies can still angle America into a good deal, win this war, and achieve real peace.

Minerals for Peace

Ukraine has, Donald Trump says, “tremendously valuable land — in terms of rare earth, in terms of oil and gas, in terms of other things.” And Donald Trump’s America wants a piece.

”They may make a deal, they may not make a deal. They may be Russian someday, or they may not be Russian someday, but [we have] all this money in there. I want it back. I told them I want the equivalent of $500 billion worth of rare earth.”

Those comments, made in an early February interview with Fox News, sent panic through the ranks of Ukraine’s supporters. Particularly in the context of bilateral negotiations with the Russians in Saudi Arabia, this had all the hallmarks of a shakedown.

And that was certainly the president’s intent. But those more familiar with Ukraine’s ample natural resources saw something else: A huge opportunity.

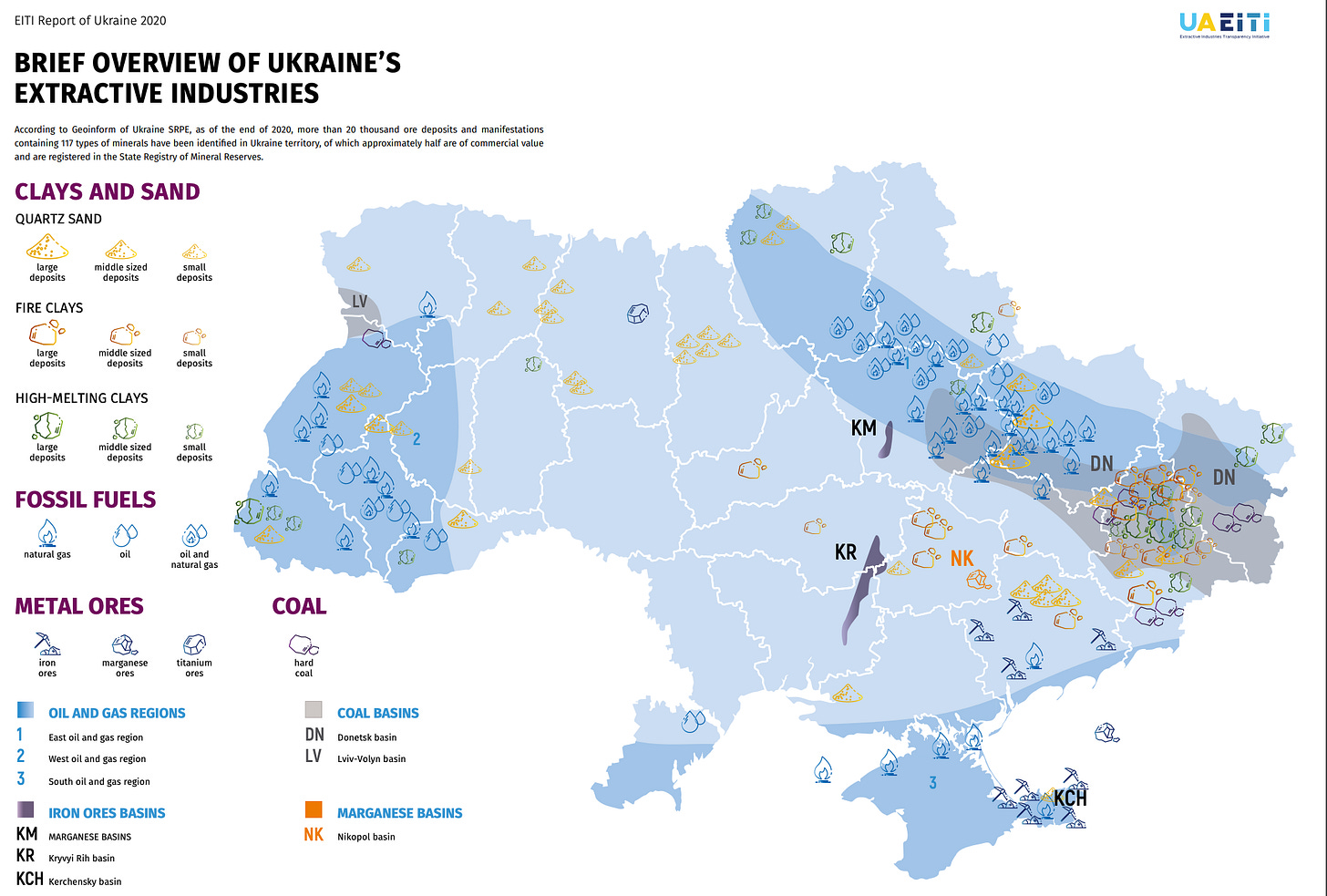

Put aside the question of rare earth minerals for a second, and just focus on more traditional resources — oil, gas, and metal ores. There’s no doubt that Ukraine possesses enormous natural wealth, but a huge amount of those riches are frozen because of fighting in the east. Indeed, there is good reason to think that Russia’s incursions into Ukraine over the past decade were precisely because it wanted to seize natural gas fields in the Black Sea, coal reserves in Donetsk, Europe’s largest salt mine, and other lucrative deposits.

Things get more interesting when you turn to some of the rarer elements present in Ukraine.

Ukraine’s massive Soviet-era steel mills have spent decades producing liquid oxygen. As a consequence, these mills generate three rare gasses: Krypton, Xenon, and Neon. That third gas, in particular, is essential for generating industrial lasers necessary to make semiconductors. While some of this production is now in Russian hands, the majority of these facilities are well behind the frontlines.

Before the full-scale invasion, Ukraine supplied 90% of America’s neon, nearly a third of the neon sold to South Korea, and a sizeable chunk to Europe and elsewhere. These exports tripled in value between 2019 and 2021, and were nearing $50 billion per year when the war began. Since the invasion, Ukraine’s exports have fallen sharply: Replaced by China.

Add in lithium, nickel, cobalt, and a grab-bag of other minerals necessary for our growing demand for phones, computers, and electric cars, and Ukraine is perfectly situated to become a massive source for our continuing tech boom.

In a perverse way, American mercantilism could give Ukraine leverage in its negotiations to end the war. Because Kyiv needs both foreign direct investment to scale-up its extractive sector and security guarantees in order to keep its territory safe, it must offer advantageous terms to any prospective partner. Russia, which now controls a chunk of Ukrainian natural wealth, likely cannot afford similarly-generous terms — even if it can, sanctions from other NATO countries will complicate that arrangement.

Kyiv knows this. That’s why it hammered out a mineral agreement with Washington last year — and then, wisely, delayed signing in a bid to let Trump take credit for the deal.

That’s why President Volodmyr Zelensky had the confidence to say that the deal would not, as Trump asserted, be a $500 billion gift to the U.S. — but, instead, involve a $90 billion development fund.

Even with these contrasting visions about what, exactly, the deal entails: Both sides signed the agreement on Wednesday. We now, thanks to the Kyiv Independent, have a full copy of the deal. [Update: Both sides were supposed to sign the agreement Wednesday.]

The text essentially creates a sovereign wealth fund, encouragingly dubbed the Reconstruction Investment Fund, into which Ukraine will need to pay 50% of natural resources revenue from its state-owned enterprises. That cash will be used to “promote the safety, security and prosperity of Ukraine.” Washington will not have the power to take money out of this fund, although the agreement contemplates the possibility of future disbursements — but it also suggests that America may want to make future investments as well.

This agreement is just a framework, and the devil will be in the details. But the agreement is good for Ukraine’s future, whilst still allowing Trump to claim that it secures a massive trove of critical resources for America.

This isn’t to say Trump’s demands are good. But the complicated resource politics have been hanging over the war since the beginning, although the financial implications have often been left unsaid. They are now on the table, and are incredibly useful in managing Trump’s obsessive transactionalism.

Critically missing from the resource agreement, however, are any security guarantees.

UPDATE: Following an unhinged performance from President Trump and his lackeys, President Zelensky left the White House without signing the mineral deal.

What Security? What Guarantees?

Late last year, I reached Yuri Kostenko at his home in Kyiv. As we spoke, he sat in the dark — Russian missile strikes had caused rolling blackouts in the capital. His line occasionally crackled and dropped out.

Kostenko is living through the failures of a deal he helped write.

A legislator in post-Soviet Ukraine, Kostenko was the chair of a committee tasked with ridding the country of its nuclear weapons. Keen to be a constructive member of the international security order, Kyiv believed in the principles of non-proliferation and hoped giving up its nukes would be a step in the right direction.

But Kostenko knew that Ukraine couldn’t just surrender these weapons. The post-Soviet block was in flux, and objects in motion are inherently unstable. Kyiv knew, too, that the imperial ambitions of Muscovy had been a constant for the past thousand years: They were unlikely to end in 1991. So, Kostenko told the world, Kyiv would only give up its nuclear weapons if the world provided “reliable security guarantees” to Ukraine.

A reliable security guarantee, he told me, means “a real range of economic, military, diplomatic instruments.” In Ukraine’s case, it would have meant a firm commitment from NATO that any invasion of Ukraine’s sovereign territory would trigger a military response from the West.

Kostenko put this deal forward, only to watch it get hammered into something unrecognizable. Ukraine gave up its nukes, but in return it got no “reliable security guarantees” — only “security assurances,” from the United States, United kingdom, and, paradoxically, Russia. The text of the deal didn’t matter: It was nothing more than a postcard from a state of delusion.

Kostenko declared in 1994: “We’re giving away pure gold and getting back ore.” With time, the Budapest Memorandum came to be known as an enormous strategic mistake.

It’s a warning that must be rattling around the halls of the Verkhovna Rada these days.

Zelensky had rejected earlier mineral deals with the United States specifically because it lacked legitimate security guarantees. Amidst some absurd rhetoric emanating from the White House, Zelensky clearly realized that a weak deal is better than no deal.

The final text of the deal mentions security guarantees without committing America to them.

“The Government of the United States of America supports Ukraine’s efforts to obtain security guarantees needed to establish lasting peace,” it reads. The only commitment that America makes to Ukraine’s territorial integrity is an oblique promise “to seek to identify any necessary steps to protect mutual investments.”

The mineral deal adds salt to this wound, however, in recognizing “the contribution that Ukraine has made to strengthening international peace and security by voluntarily abandoning the world's third largest arsenal of nuclear weapons.”

Washington is highlighting its past failures as it repeats them.

This shouldn’t surprise us, however. It was abundantly clear from the outset of Trump’s campaign that he has no interest in providing protection for the world any longer. That should have been a direct invitation to Europe and Canada to step in and figure out an alternative.

“You have to design new principles of Ukrainian security,” Kostenko told me. “From the period [between the possible] end of war, next year, and Ukraine’s participation as a state in the collective system of NATO.”

But, today, we have never been further away from those principles. Trump has effectively slammed the door shut on Ukraine joining NATO. The other NATO countries, pressed repeatedly to explain what security guarantees they can offer Ukraine, have struggled to explain what they could offer, beyond the status quo.

Before any security guarantees get offered, however, there needs to be peace.

Peacemongers and Peacemakers

In late 1917 Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, the 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, penned a letter that caused quite the stir.

“We are not going to lose this war,” wrote Lord Lansdowne, former war minister and governor general of Canada. “But its prolongation will spell ruin for the civilised world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weighs upon it.”2

The Lansdowne Letter, as it’s known, makes a whole-hearted pitch for peace, and for ushering a new spirit of global cooperation, not war, to settle disputes. Worse yet, he warned, if the war continues it could destroy humanity altogether. “The prostitution of science for purposes of pure destruction is not likely to stop short,” he warned. The aim of security, he argued, ought to come ahead of the need for reparations.

It’s hard to disagree with the sentiment. But, Lansdowne noted, Germany was unwilling to actually negotiate peace. So the Allied powers needed to entice the Kaiser to the table. "When it comes to the wholesale rearrangement of the map of South-Eastern Europe we may well ask for a suspension of judgement,” he continued.

In other words, Lansdowne was suggesting surrendering half of Belgium — and huge swaths of other territory — to the central powers, as a consolation prize for losing the war.

This view had a prominent critic in Winston Churchill.

“Let us not delude ourselves by thinking that there is any substitute for victory,” Churchill wrote to his constituents. Why should the people of Europe, who were beating back German aggression, bend a knee to the “hollow pomp of German military assertion?” Churchill asked. “Are we to doom our children to accept for all time the Germans at their own valuation, at their highest valuation, at their most extravagant valuation; to stamp these false values forever upon the world & to blot out from the account our immense, and if we give them play, overwhelming resources? To do so will be to defraud & defile the destiny of man.”3

In the end, Churchill was right about the need to keep fighting: The Allies won absolute victory a year later, and Europe was liberated. But Lansdowne was right about the need to prioritize global order over national grievances, even if his roadmap to get there was faulty. We’re still learning these lessons.

Brian Meford, a Kyiv-based analyst, picked up on the competing visions of Lansdowne and Churchill when he pondered the difference between peacemakers and peacemongers in 2023.

“Many Westerners see such a ‘land for peace’ solution as a means to appease Russia’s imperial ambitions,” Meford wrote. To do so would obliterate the post-WWII consensus that borders cannot be redrawn by force. “In effect, this would be a tacit endorsement of Russian aggression as a legitimate method of gaining land and recognition. That alone should be a non-starter for any policy official.”

But, more than that, a short-term ceasefire — meant more as a reprieve for the people funding the war, not those fighting it — is likely to guarantee more long-term bloodshed. Russia’s ambitions, Meford noted, are on Odesa’s warm-water port and Kyiv’s historical significance to the Russian empire. Its territorial ambitions only continue from there. Nobody but Russia wanted this war, but the only way to end it for good is to win.

“The swift delivery of justice is necessary to end the war and preserve peace,” Meford writes.

I met Meford last year in Kyiv. A longtime Republican, we sat and chatted in dismay about what had happened to his party. At least, we counselled ourselves then, Ukraine’s defenders remain the majority in the party.

Unfortunately, that tide has turned. The GOP now believes that either Ukraine cannot or should not win this war, and that she ought to be carved up in the name of expediency. Some believe the recognition of these new borders require, to borrow Lansdowne’s language, “a suspension of judgement” whilst others are all-too-happy to recognize eastern Ukraine as Russian territory.

Ulana Suprun, Ukraine’s former minister of health and a longtime friend, sent me Meford’s essay this week and sent along some of her own thoughts about Ukraine’s current predicament and America’s growing cowardice.

A peacemonger is willing to tolerate dictatorships, industrial scale murder, and consign a people to genocide because of a fallacious understanding of peace as simply the absence of conflict. But conflict cannot be eradicated, it’s simply a part of life.

For the longest time, western thought has held and promoted the idea all wars eventually end because the parties arrive at peace as if it were a destination, like a stop on the subway. This is the height of hubris as even a cursory look at human history suggests peace has been elusive.

Peacemongers would like everyone to think peace is a destination. And they would like to arrive at this destination sooner than later, regardless of the consequences. Curiously, they often echo the rhetoric of those who pursue war.

An ideal peace entails a fair and just end to the war, not simply the cessation of open conflict. In reality, the ideal is almost impossible to achieve and real peacemakers know this, which is why they speak about establishing collective security. It is the protection former colonies of the Russian Empire were seeking when they applied for NATO membership. In the face of collective security, the crime of aggression is unlikely to succeed or even to proceed.

America is led by a peacemonger, whereas Europe and Canada are led by peacemakers. We shouldn’t pretend like those are the same thing.

I do not know what comes of Trump’s repulsive attempts to surrender on Ukraine’s behalf. But I do know that angling for peace, even the illusion of peace, will be harder than Trump thinks.

Consider that Russia has repeatedly rejected a land-for-peace deal. The Kremlin has continued to insist that a deal can only be done if Ukraine surrenders hundreds of kilometres of more territory, millions of people, and submits to de-Nazification, de-militarization, and permanent neutrality.

General Keith Kellogg, ostensibly Trump’s Ukraine envoy, knows all this. That’s why he worked to include Ukraine in the process, and advocated for applying pressure to Russia to force an equitable deal. That’s also why Kellogg has been marginalized and denigrated by Vice President J.D. Vance and nepobaby-of-a-nepobaby Donald Trump Jr.

Trump may yet surprise all of us and secure a genuine deal that brings about a lasting peace. Or perhaps he may come to realize the folly of doing a real estate deal to end a war and realign himself with Ukraine in order to achieve victory and real peace. More likely, I think, he is negotiating the terms of his own comfort.

The peacemakers shouldn’t let him.

UPDATE: See?

That’s it for this week’s dispatch.

If you want to read more about the tricky nature of security guarantees for Ukraine, you should read this in-depth piece I wrote on the question for Foreign Policy.

If you haven’t already, I also suggest you read some previous Bug-eyed and Shameless dispatches on Ukraine. (Dispatches #92, #93, #94, #122)

For the Canadians, I’ve got a mini-column on the disappointing vagueness coming from the people set to succeed Justin Trudeau. Expect to see another column in Saturday’s paper about our old friend Peter Navarro. I also chatted about Navarro with Arshy Mann over at The Hatchet, so go give that a listen.

Until next week!

Photo and video by Andriy Yushchak.

Daily Telegraph, Nov 29, 1917.

Winston S. Churchill : World in Torment, 1916-1922, Martin Gilbert (2015)

There's an old Russian proverb that peace mongers should consider carefully. "Eternal peace lasts until the next war."

You said both sides signed the agreement Wednesday (Feb 26). If that's the case what was with the despicable display in the White House at the end of the week? I thought that they were going to sign the agreement and then Trump and Vance instead used the opportunity to try and berate Zelenskyy, ending with no deal signed?